Slip of the Tongue

We ask each of our interns to choose a book from our catalog and review it. Hayley chose Katie Haegele’sSlip of the Tongue: Talking About Language.

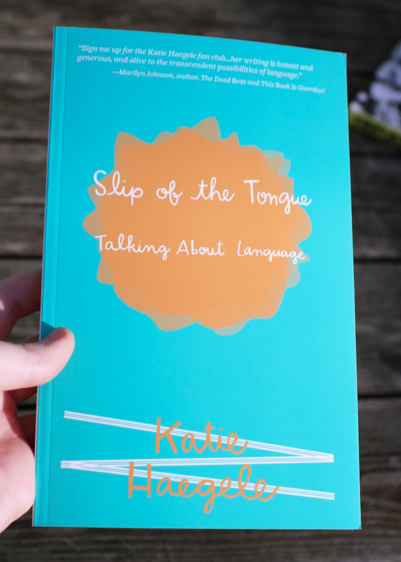

I knew I was going to enjoy Slip of the Tongue from the moment I held the skinny teal book in my hands. The bookish-English-major-nerd within me was immediately taken with Katie Haegele’s collection of essays, which attempt to make sense of the world through our collective and individual use of language. What I hadn’t anticipated was just how captivating I was going to find the author and her book.

I knew I was going to enjoy Slip of the Tongue from the moment I held the skinny teal book in my hands. The bookish-English-major-nerd within me was immediately taken with Katie Haegele’s collection of essays, which attempt to make sense of the world through our collective and individual use of language. What I hadn’t anticipated was just how captivating I was going to find the author and her book.

Haegele’s memoir is intelligent without being unapproachable, particularly considering its focus on something as academic as linguistics. This is in part due to her distinctively personal voice. Her short essays, insightful and clearly articulated, are utterly conversational – creating an intimacy with the reader, but with a surprising sense of informality.

Reading this book truly felt like a conversation you fall into with someone you didn’t previously know so well, but somehow become instant best friends with; staying up all night fervently discussing life, without realizing the sun has left and come back again.

Underlying the entire work is Haegele’s love of language. It radiates from each page, seeping into every story told—whether articulating the peculiar history of graffiti in Philadelphia or expressing the sharp pang she feels at the glimpse of her father’s coffee mug that reads “Pizzazz,” the single surviving relic of him following his death. I really enjoyed her various observations on language because, despite her reverence for it, she is never precious about it. Haegele isn’t as concerned with preserving language as she is with observing the ways it has transformed. Old ways of communicating aren’t necessarily superior to current forms. She doesn’t mind the formation of so-called ungraceful words like “chocoholic” or the decline of cursive. Language isn’t stagnate, it effortlessly morphs and changes with time. But for Haegele, this malleability makes language all the more important. Words are arbitrary—they’re random sounds we’ve assigned specific meaning to—yet, significantly, they’re formed out of an essential human need to communicate. I love this idea, that language could be haphazardly formed while at the same time shaped for a distinctly human purpose.

I was particularly drawn to the essay “Another Word for Lonely,” which reflected on a few almost-synonyms of the word nostalgia found in different languages and cultures throughout the world. From a young age, I was fascinated with the past. I set out to find fossils in my backyard or begged my mother to buy me yet another twenty-five cent Victorian glass figurine. I loved these objects, and I would often dream of experiencing an older, grander time. They made me feel closer to a past I deeply longed for—admittedly a fictional, highly romanticized version of the past. But it was real to me, and I often feel that yearning still.

So when this essay explored different words that varyingly express this nostalgia, I was immediately captivated. There was some comfort found in reading the definitions of saudade, kaiho, hiraeth, and sehnsecht. Sure, the word saudade doesn’t diminish my romanticism and kaiho doesn’t make me feel any less lonely, but having the language to more easily describe that indefinable yet universal “hypochondria of the heart” at least makes me feel a little more understood. It’s nice to know I’m not alone in feeling or striving to describe these nostalgic sentiments.

And that is what is so great about Slip of the Tongue: it is so very human. In analyzing language Haegele is attempting to understand her own humanity, and she invites the reader into her life to make their own self-discoveries. It is so much more than a book about language; it is a book about life.