Call for Submissions for Neurodiversity zine series

Joyce Brabner passed this week, one of the most important progenitors of rethinking comics and a very influential person in my personal life for decades.

I watched her struggle for name recognition despite innumerable accomplishments of her own, seemingly because she didn’t take the famous surname of her husband, Harvey Pekar. I cannot tell you how many times I watched her ask “Are you familiar with me?” in a clarifying sense. Indeed, in 2009 when she called our office, she didn’t recognize my voice and asked “This is Joyce Brabner, do you know who that is?” We hadn’t talked in a few years so I was rather startled and it took me a minute to return to that time in my life.

Joyce had no shortage of personal accomplishments on her own, dating back to before I was born. She created prison literacy programs and used the power of comic books to impart what was going on in the real world in a way that was less threatening. She collaborated with Alan Moore and did activist work around AIDS, animal rights, and child abuse. If she was here she’d be insisting on clarifying many of the finer points of each of these things before we moved along the presentation. To most people, she is Hope Davis’ version of her in the film American Splendor. Fear not, upon first mention, she will tell you each and everything that she finds inaccurate about that depiction. And it always made me smile.

Later that day, when I said “I spent three hours on the phone with Joyce Brabner,” Elly’s mind exploded. “How do you know Joyce Brabner?” Burying the lede just like Joyce taught me, I said “We go back” and left it at that. To many, when Hollywood makes a film about your family, you enter the limelight in a new way.

I remember in 2001, she called to say “They’re making a movie about us. You should invite us to the Portland Zine Symposium. HBO will pay. We don’t need money. Just an invitation.” I didn’t believe it. Why would HBO make a movie about the most normal family on Earth? But it was great, because after that I really got to see Joyce shine for the next five years. Their family was everywhere, with Joyce in front, negotiating the deal, Harvey standing behind her right shoulder, and young Dani behind Harvey’s right knee. It was almost like a defensive position while Joyce made things happen and made sure that they were treated fairly in all of their dealings. In the classic lineup, Joyce was the one that I related with the most. We have both been painted as difficult because we’re the ones that the logistics hang on and other people rely upon us to be resolute and firm. The last time that I saw them in that era was at the Wisconsin Book Festival in 2006 and then we lost touch for a few years, perhaps because they faded from the limelight. Harvey had struggled a bit on stage that night. We didn’t talk for two years afterwards.

Joyce was of course much more than the movie cartoon character. She was a masterful conversationalist and remains a very important inspiration in so many aspects of my life. She believed sturdily that if someone was in need of help and willing to give 50%, she would give the other 50%. It was a powerful lesson as a young person, in a city that yet felt hopeless, where people were willing to turn the other blind eye to suffering. But I made an effort to ring her up when we were in Cleveland. She taught me to aim higher and be more ambitious.

It didn’t even occur to me until writing this that she is likely where I got the idea not to have kids because I am busy raising other people’s kids. She would have a better way to package that sentiment, but the ideas are the same. And it’s a powerful one that I still carry with me until today. We were peas in a pod in many ways. During one lunch, we both had someone else on-hand to write down notes for us to have later. Once we both noticed this, we realized how funny it was.

When people in the comics industry were dismissive of me, she would call them up and tell them to feature me. And they would listen. She told Publishers Weekly to do a feature about Microcosm in 2011. And they did. She told Diamond Comics to give us another chance. And they did too.

In 2014, she called me as she walked out of the Farrar, Straus and Giroux offices in NYC. “I don’t want to work with them anymore. I want to work with you.” She dedicated her 2014 book, Second Avenue Caper, to me. She sewed and sent me a custom Harvey doll with the Microcosm logo as the chest piece instead of American Splendor. Ten years later it lives in my window, next to my Henry & Glenn dolls. In 2015, she wrote the foreword for my memoir and said very kind things about me publicly at times when I was struggling.

When we hung out in 2019, it was the first time that I really saw Joyce struggling. She had always been so unbelievably unstoppable and powerful. Joyce was younger than my parents, but time was as much a constant as the trials and tribulations and her ability to overcome. She got better, and we resumed our jovial banter.

We published her book, Courage Party, minutes after COVID began in 2020. It is a powerful book for kids about how to navigate life after violence. We were largely reliant upon library sales just as their budgets shriveled up for the pandemic. Courage Party, while not commercially successful, brought us another one of Joyce’s gifts in artist Gerta O. Egy, who we have gone on to do many books, decks, and comics with.

Undaunted by one unsuccessful title, Joyce began proposing new books to us. She wanted to write a history of gangs. And then years later, she called her editor and suggested that the story of gangs wasn’t her story to tell. Joyce was capable of changing her perspective too. She had innumerable children’s books in the wings. She saw her greatest work ahead of her.

When I discovered that Our Cancer Year was out of print, I called her and she was shocked to learn this. I looked it up on Bookscan and I swear that the sales were over 200,000 but when I looked again years later, after NPD turned it into DecisionKey, the numbers dropped 95%. We spent the past few years creating a situation where she would give me power of attorney to leverage all of the out of print books back from the Big Five publishers who had the rights but took the books out of print. She liked the idea that, unlike a lawyer, she didn’t have to pay me. I did it because I cared about the people; the work; the legacy. In many cases, the publishers didn’t know that Harvey Pekar had died in 2010.

I followed up with her a dozen times. For years, we have been on the brink of reissuing quite a few books that are maddeningly out of print and it was “I just need to conquer this cancer first and then we’ll deal with that.”

Most recently she got excited about a deal to publish the first four American Splendor comics in Brazil for the first time. She called me to ask if we’d re-issue the same book in English simultaneously. Of course, I heartily agreed. She said that she would connect me with the other publisher to work out the details. I waited.

I talked to her on the phone a few weeks ago and we made some plans to have lunch in October. She closed our phone call to say “Get all of the time with me now that you can. I don’t have much left. I’m just joking. But not really.” I wasn’t sure how to take it. Joyce had a dark and heavy humor. And like all good humor, it’s couched in reality. It resonates because it’s very real, revealing a greater truth that we cannot say in other language.

I knew something was wrong when Joyce still hadn’t connected me to the Brazilian publisher a week later. She doesn’t leave loose ends, even at the worst of times. She doesn’t leave money on the table. I figured that I’d give her a little more time. Turns out that we didn’t have it.

To the very end, she was worried about setting up each project to benefit other people. She taught me so much about mutual aid as a young person. She built a nation of imitators but there can only be one.

Usually, when we tell strangers that we work in publishing, they picture us crafting the latest bit of editorial brilliance from an emerging, young mind over a candle-lit typewriter. Or they mourn the death of the publishing industry with some imaginary dreck like “nobody reads anymore.”

For better (and some days, for worse), paper books remain more popular than ever, especially with young people. This leads to an ever-increasing volume of warehouses, shelves, racking, paper, trucks, and…safety ladders. And this leads us to a snapshot of one of the key roles of a publisher in any era: negotiating with suppliers and figuring out material flow logistics.

We organize our warehouses so that the most popular books are on the floor for easiest access. As books get older and less popular, they are placed higher and higher in the stacks, until they require a ladder to retrieve.

During the pandemic supply chain crisis, we were at the mercy of material shortages and manufacturer delays. It took three times as long as usual to print a book. But it wasn’t just books. On October 18, 2022, we attempted to order four more safety ladders from Webstaurantstore. The estimated delivery date was “March 2023.”

“Wow,” I thought. “That is a long time to wait for four ladders. But we need ’em.”

We placed an order for shelving parts at the same time. Another $2,324.99 of your hard-earned money was spent on more of our behind-the-scenes infrastructure.

We waited. On November 7, 2022 we were surprised to receive a delivery from a company called Ballymore. We received no tracking information or advance warning that a delivery was coming, including no information about what was in the order. We were not given a Bill of Lading (the legal document that shows what is contained in a delivery), we weren’t told that this was part of our Webstaurantstore order, and the delivery driver did not even request the standard signature confirming delivery or allow time for us to inspect the boxes before he left. Upon opening the four boxes on the pallet, they proved to each contain one out of four pieces of a single ladder, which needed to be assembled. And we’ll never forget that, because assembly seemed to take all day.

Due to the lack of communication or notices, we were baffled. “Weird. I guess materials are in such short supply that they are going to send these one at a time?” I thought. Honestly, I didn’t think much of it—we frequently receive items from a single order in multiple shipments over a period of time. Our online Webstaurant store order was not marked as complete, so we assumed that the other three ladders were coming in March 2023, as quoted.

We had still not received the remaining three ladders when we were scheduled to on March 21, 2023, so we followed up with the Webstaurantstore. Instead, we were told that it was too late to notify them of a shortage, since it was more than 5 days since the delivery of the single ladder. They updated our shipping status to “delivered.” We argued that it was less than five days since the items were expected to be delivered. They told us that their records showed that we had received four ladders, none of which should have required assembly and insisted that three ladders were lost in our warehouse. “Look around and you’ll find them” was their solution. It was as insulting as it was baffling, as if we would contact them before “looking around” and had somehow managed to misplace three seven-foot ladders. They said there was nothing that we could do.

When it became clear that Webstaurantstore’s claims were illegitimate and they were not going to send us the ladders that we had paid for, we filed charges with Mastercard on March 28, 2023 because the merchant was not interested in resolving the matter. On April 4, 2023 Mastercard attempted to close the case in our favor but Webstaurantstore persisted.

On May 15, 2023, Webstaurantstore responded to the complaint but did not send sufficient documentation to dispute the refund. Then a week later, on May 23, 2023, our claim with Mastercard was denied, as, in the words of the Mastercard rep, “Usually a merchant does not go this far or provide this much paperwork…unless their ability to accept Mastercards due to a volume of disputes is being threatened.”

How did they do it? Webstaurantstore falsely asserted that we had signed for the shipment and they “found” the bill of lading that had disappeared. Suddenly, they had “proof” of shipment to provide and claimed that we had waited past Mastercard’s 90-day window after delivery. They sent shipping proof for the single ladder as “four pieces,” claiming it was four ladders. They adjusted facts and timelines as was convenient for their argument. They argued that the estimated delivery timeline and lack of communication were irrelevant, so the 90-day window would be calculated from the date of the original order in October. They tried to claim that the unsigned bill of lading was a legal document “proving” delivery. If it was, we had no way of knowing what was allegedly contained in this delivery because it had never been provided to us.

On June 1, 2023 we filed a second dispute with Mastercard, citing that 90 days had not passed since the delivery window, the shipment in question did not contain all of the items that we ordered, there was no communication provided to us that Webstaurantstore believed the transaction was complete, and the bill of lading was never signed or delivered, so we had no way of inspecting it for damage or shortage, as is customary and the purpose of these documents.

On June 29, 2023 Webstaurantstore again asserted to Mastercard that we do not have charge dispute rights through, as the Mastercard representative put it “Barraging us with a sheer volume of information and paperwork.” but again falsely claiming that the 90-day dispute window after delivery had already passed when first the dispute was filed. This time, Webstaurantstore went so far as to claim that the date when we placed our preorder was actually the date that the items had shipped.

We looked for other ways to resolve the situation. And this is where things became much more insidious. Since Webstaurantstore is based at 2205 Old Philadelphia Pike Lancaster, PA 17602, we filed a complaint both with the Better Business Bureau (BBB) and the Pennsylvania attorney general. Both organizations seem strangely powerless and act more like dispute mediators than having any authority over a private business (“participation in the Bureau’s mediation process is voluntary for both sides, and we cannot compel a business to agree to a solution.”) that apparently does billions of dollars in annual revenue for the state.

BBB suggested filing notices with the Attorney General’s Office Bureau of Consumer Protection in both Ohio (where they were delivered) and Oregon (where we are based), but these organizations disagreed that this was appropriate. So we explained Webstaurantstore’s deceit to Mastercard once more, who agreed that they were obfuscating the facts and attempted to try again.

We repeatedly called the Webstaurantstore customer service number, (717) 392-7472, thinking that if this company is as legit as they claim, they would understand that a perfect storm of events had gone wrong and resolve it. Instead, we were issued a concerningly lengthy claim number, 20231100079631, which would indicate that we are close to their 80 thousandth case of not delivering what someone paid for (or if you ignore what is likely a date, more amusingly, their 20 trillionth). Indeed, each customer service person variously implied that we were confused or lying. Perhaps this “perfect storm” was a feature, not a bug?

Webstaurantstore does not appear to have the ability to be reviewed on Google, but does have a fraudulent page of glowing “google reviews” that they maintain themselves. Clever, misleading, and somewhat baffling.

While the Pennsylvania Attorney General said “you are free to pursue a lawsuit privately,” it turns out that this isn’t entirely true. You see, Webstaurantstore has a particularly shocking “Terms of Service” document:

“You agree that any disputes and claims related to or arising from these Conditions of Use and/or your use of this website, including disputes arising from or concerning their interpretation, violation, invalidity, non-performance, or termination, will be resolved through final and binding arbitration under the Rules of Arbitration of the American Arbitration Association applying the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, instead of in court. An exception is that you may assert claims in small claims court, if your claims qualify. To begin an arbitration proceeding, you must file a Demand for Arbitration with the AAA, according to the AAA’s rules. Payment of all filing, administration, and arbitrator fees will be governed by the AAA’s rules. We will reimburse those fees for claims totaling less than $10,000 unless the arbitrator determines the claims are frivolous. Likewise, WebstaurantStore will not seek attorneys’ fees and costs in arbitration unless the arbitrator determines the claims are frivolous. You may choose to have the arbitration conducted by telephone, based on written submissions, or in person in the county where you live or at another mutually agreed location.”

This sounds reasonable until you learn that the AAA arbitration fees would cost us a total of $1,725, for a dispute of items costing $1,142.59. It appears that these policies are intentional. Particularly after we learned about the multitude of lawsuits that Webstaurantstore receives from its own employees about alleged illegal labor practices, or as one former employee filed in a lawsuit, they “have not been provided real access to arbitration.” This was very concerning, as is the principle of the matter and our commitment to preventing this from happening to others.

Despite the fact that we did not sign a contract, this is significantly more expensive than a lawsuit costs to file. Fortunately, their terms of service are probably not legally enforceable.

Since we were not made aware that Webstaurantstore erroneously claimed that the order was delivered in full and they did not communicate this fact to us, we remain incapable of fulfilling and agreeing to the terms of sale. Hence, we were not able to notify Webstaurantstore about the delivery shortage within their timeframe because they changed the delivery time frame of the delivery without notifying us of this change.

As I began to research the company, I learned that numerous labor disputes have risen to the level of lawsuits, for everything from retaliation for attempting to collect overtime pay to multiple cases of civil rights discrimination. They also like to argue about intellectual property and have been sued for this as well. And it appears that we were not the only ones who suffered because of their misleading business practices.

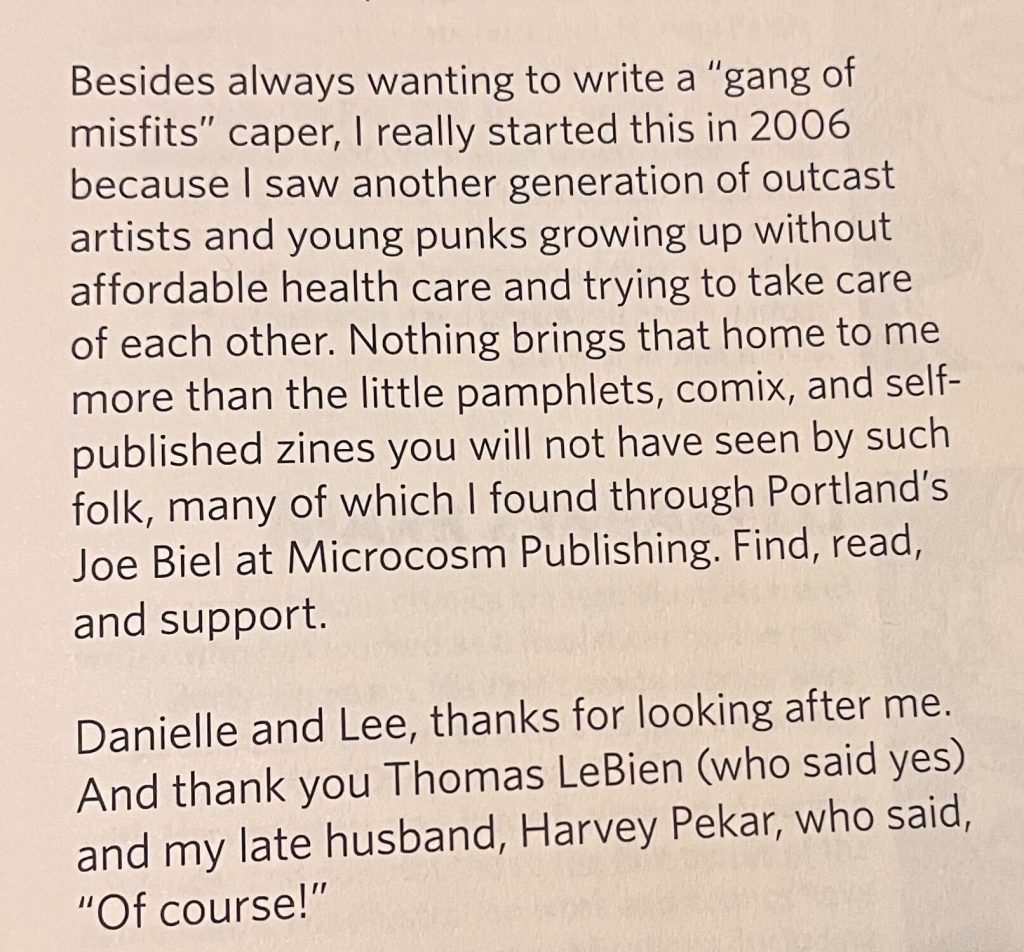

Who was this Webstaurantstore? It appears that their game is controlling the SEO around all restaurant equipment, and they are great at this aspect of their job:

One aspect of their strategy is posting innumerable “articles” that would turn up when you search for “Webstaurantstore fraud,” and instead of the hundreds of entertaining stories of customers not receiving what they paid for and third parties blaming each other, you’ll receive “Webstaurantstore’s guide to preventing fraud at your restaurant.” A Forbes article touts that Webstaurantstore earns more in a day than we do in a year.

A friend pointed out the obvious: Microcosm has great SEO so the area where we could best protect potential future customers is through adding this story to their search results. We simply wanted the items that we paid for or a refund. Instead, nearly two years later, we’ve sunk hours into efforts at basic customer service interactions.

We’re still weighing our next steps. We have either until October 2025 or March 2026 (depending on Webstaurantstore’s obfuscations) to escalate the dispute legally. You might be thinking at this point, “Wow, Microcosm is really obsessed with this ladder thing, maybe they should move on.” Are the time and expense worth it to us? Maybe. Definitely not in terms of money—any legal settlement would need to be much larger than the bilking of the ladders in order to cover the time and costs we’ve already sunk into this issue. We could just let this go—we’re large enough at this point that the loss of three expensive ladders won’t sink us. But even just five years ago, it would have seriously compromised our ability to make payroll and we wouldn’t have been able to do a thing about it. We know we’re not the only people who’ve incurred losses by dealing in good faith with this company. We don’t have limitless resources, but it still seems worthwhile to use some of them to try to hold accountable a giant company that does twice our annual revenue every day but won’t make it right when they mess up.

As book publishers, we all know what it’s like to struggle in the shadow of a giant online retailer that plays dirty and seems to relish endless growth at the expense of everyone else in its ecosystem, including its customers. When people ask us what our day to day job is like, they don’t imagine a years-long dispute over ladders, but what else is there? A ladder helps us safely and quickly get you the obscure book you took a chance on, it helps us protect our workers and our colleagues, it helps us always reach higher.

Post Script: Within 24 hours we heard from numerous businesses who experienced the same phenomenon when attempting to order from Webstaurantstore; one of which went out of business afterwards.

In 2022, Microcosm was Publishers Weekly’s fastest growing publisher, based on our growth of 207% between 2019 and 2021 (check out our annual reports for 2019, 2020, and 2021 for more on that wild ride)! Then in 2023, we were Publishers Weekly’s #3 fastest growing publisher mostly because of our significant growth in 2021.

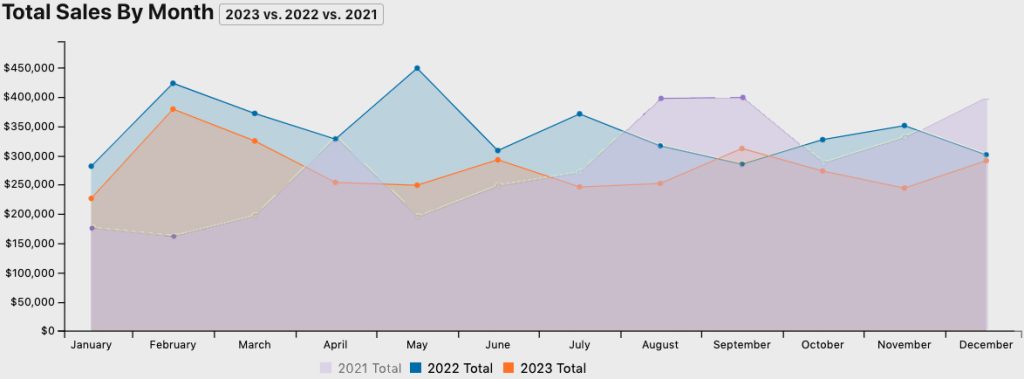

Over the previous twelve months, we had yet another wild ride. We saw a fork in the road and we chose to self-finance our meteoric rise, reinforce and shore up systems rather than force aggressive, continued growth. As a result of those choices and apprehensive and uncertain retailers fearing a recession, our sales fell -18.67% in 2023. However, 2023 still saw 3.4% growth over 2021. There is much conjecture in our industry that 2021 was an abberration; a “pandemic bump” for books, but we are continuing to grow past it.

We remain fiscally solvent and financing growth with cash; owing $449k and owed $664k, despite purchasing a third warehouse with cash in 2023.

Most of this year looked like a cookie cutter “2022 minus 18.67%” until September, when it looked like we’d make up for eight months of reduced sales. But retailers remained apprehensive and reactive, anticipating a recession that never came by having undestocked shelves.

We published 39 new books in 2023, with 18 more coming this Spring and 21 more coming this Fall!

We’re excited to resume conventions in a few weeks with PubWest, Winter Institute, and Vegas Market.

Our newest warehouse in Cleveland handles 67% of our shipments and 78% of our receiving. Interestingly, October was a record shipping month and overall, we saw that orders were on par with 2022’s busy holiday season—our best holiday shipping season ever—so that seems fantastic. And it looks like this will inform cash flows for Q1.

One store reported, unabashedly “My accountant told me that the more books that we buy from you, the more that we sell for the holidays.” And the buyer has responded in turn.

The major difference this year is that things never stopped (which is consistent with 2020 and 2021 but not 2022). We received the largest order that we’ve ever seen on Christmas Day for over 5,000 different titles. The same store sent two additional orders in the same week, with promises of two more yet to come. Our marketing and sales departments are working closely with them to build these up.

We’ve seen that responding to the individual needs of each retailer and what they need from us is fundamentally what grows those sales. So it’s largely listening and being responsive. e.g. We were understocking in Q2 of 2020, anticipating recession, and stores complained that we were sold out of titles they needed so we responded and found a middle ground…until it was clear that sales were not slowing at all. But it took four months to bear out that data.

It remains clear that the more warehouse space that we have, the more books that we can sell. So we continue to inch in that direction—just not too fast so we can prevent cash and protect everyone’s jobs.

The most interesting thing here is that we have built our systems so that we don’t have “slow months” or “increase returns exposure” in January and February—because they are some of our busiest months. Our total returns for the year were a scant 1.48%.

Our success continues to be based 50% on what we publish and 50% on how we publish. Meaning that, of the 12,000 stores that we work with (1788 of which we added in 2023), about 25% of them purchase all of their books from us and so our salespeople don’t stick them with hyped books that they cannot sell. 99% of our books are evergreen, so we aren’t fighting a timer to make them burn bright before they fade away. Best of all, the practical skills and values in our books are what the world has wanted for at least the past 28 years. Probably longer. The need remains vast. So does the interest. And we really focus on how each book can bring meaning and purpose to someone who feels lonely in the world.

We added our eighth co-owner this week, though all profits are shared with our entire staff. In 2023, profit sharing equated to an additional $1.50 per hour per person for the entire staff and we were able to increase our budget for wages by 26.67%. We increased our paid time off benefits and also offer insurance to our staff (though that became 67% more expensive in 2023).

And if you really want to get into the nitty gritty of publishing, check out our podcast.

But before we wear you out completely, let’s take a look at the numbers.

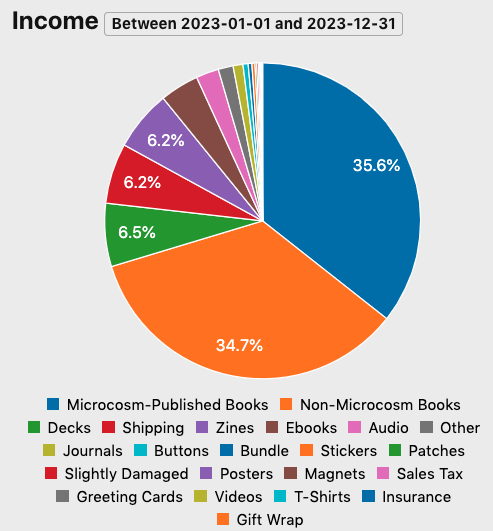

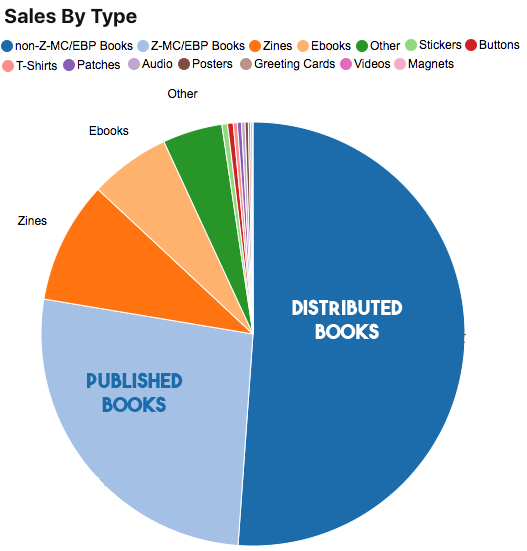

Our total sales for the year were $3.8 MILLION DOLLARS, with our own publishing comprising about 64.4% and ebooks comprising 4% of our sales:

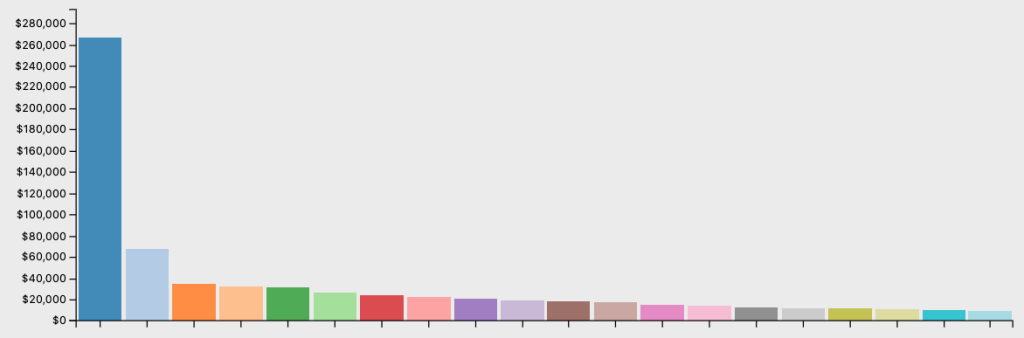

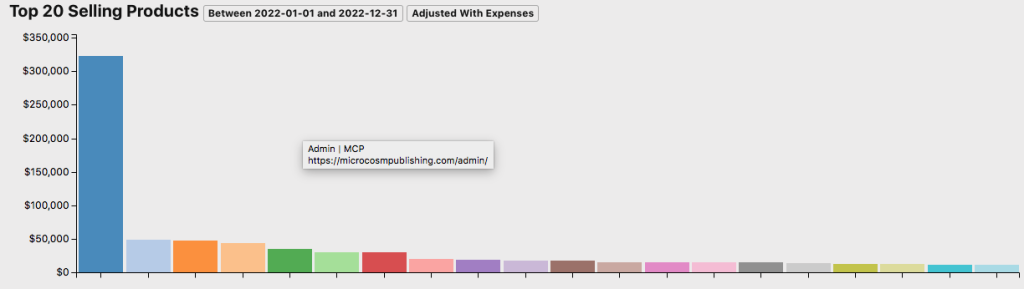

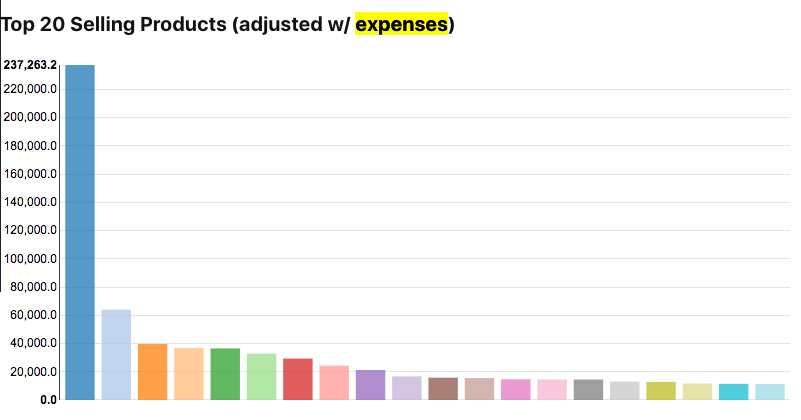

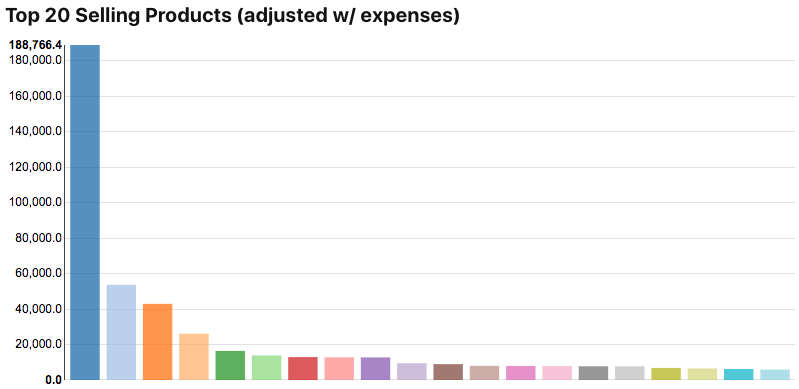

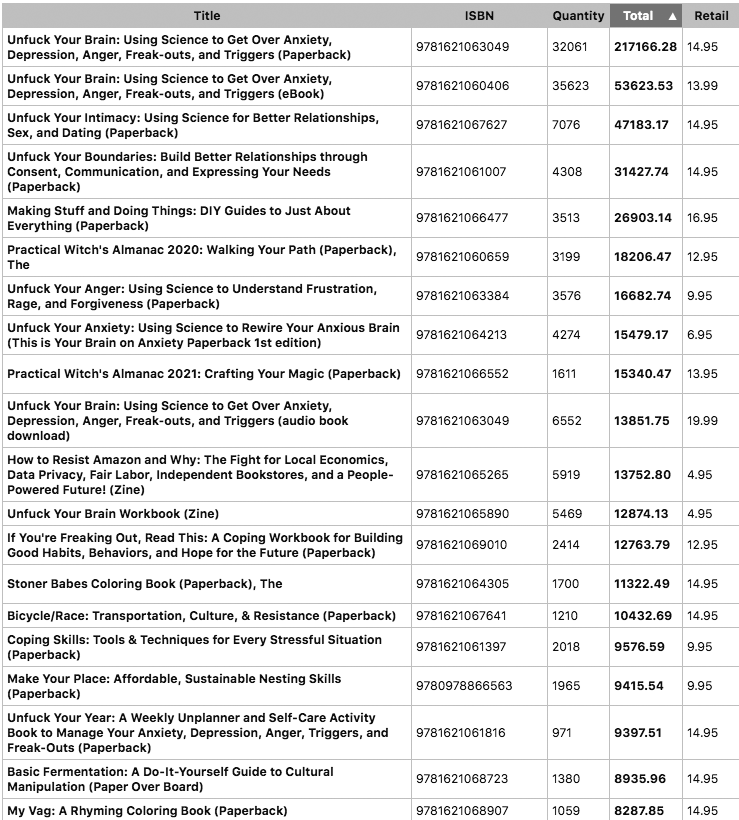

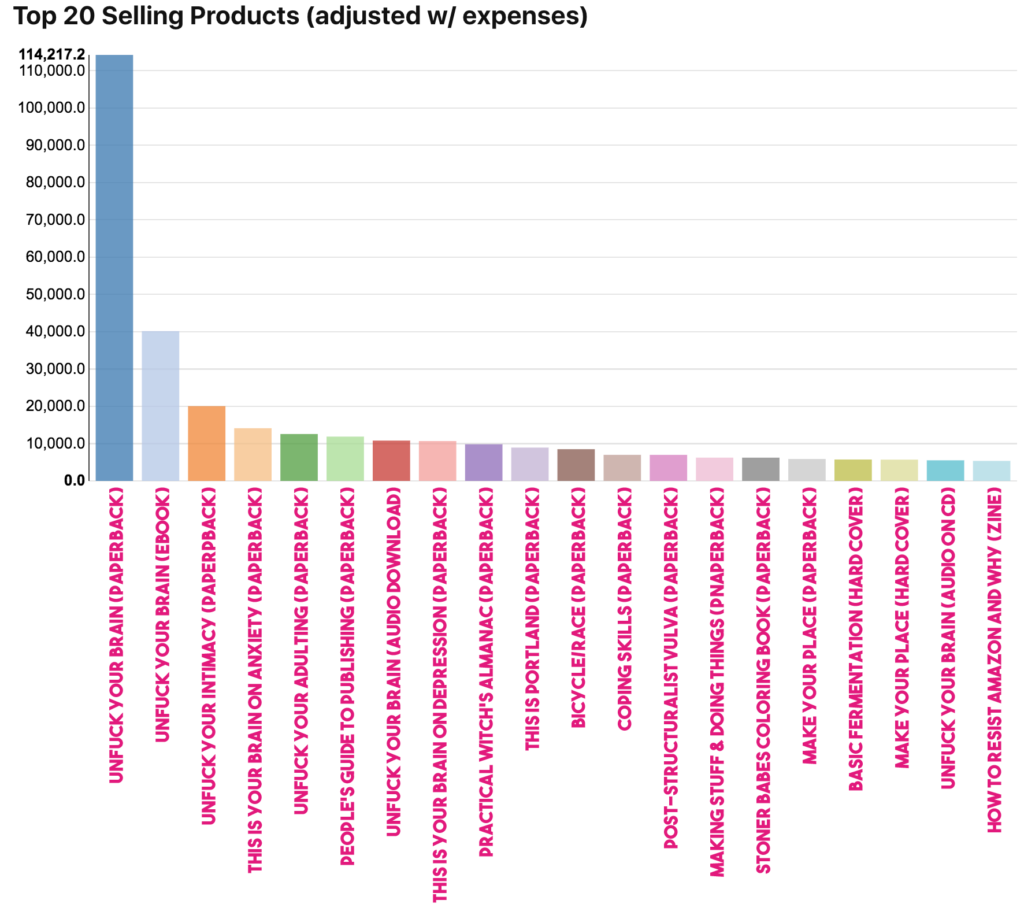

And here are our bestsellers for the year by dollars earned (minus expenses like printing and cover design):

UNF*CK YOUR BRAIN, which we published in 2017, is still outselling the following twenty books—combined. This one title continues to comprise 9.57% of our total sales. Even if you ignore this aberrant title, it was a phenomenal year. We published 39 new books and over twice that many zines. And healthfully, 95% of the titles selling in the top 20 were published prior to 2023, meaning that the sales are “sticky,” the books will continue to sell for years to come (and we expect our 2023 publications to shine this year).

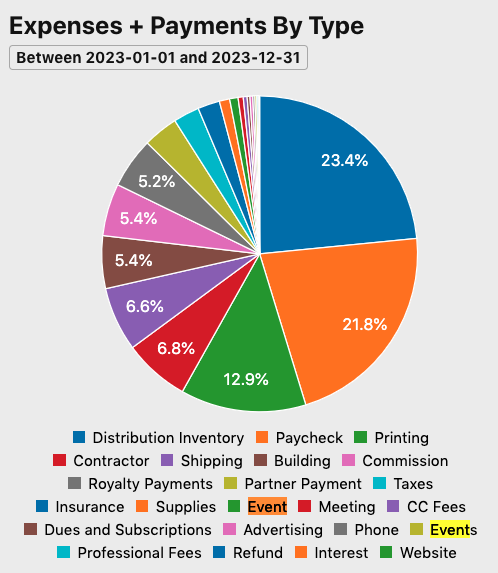

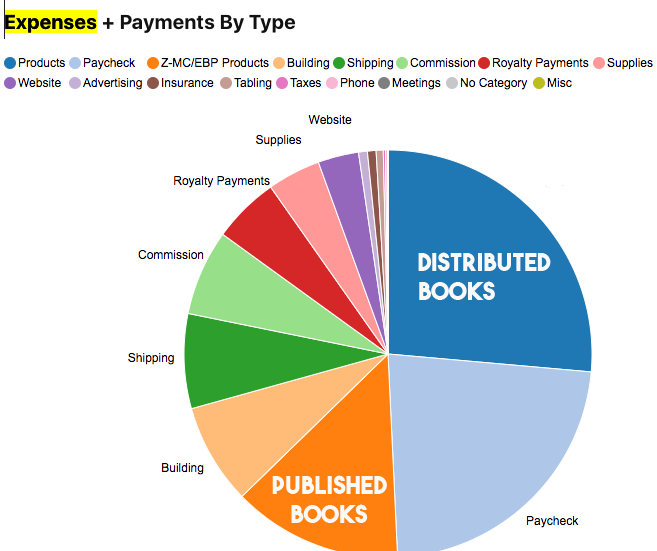

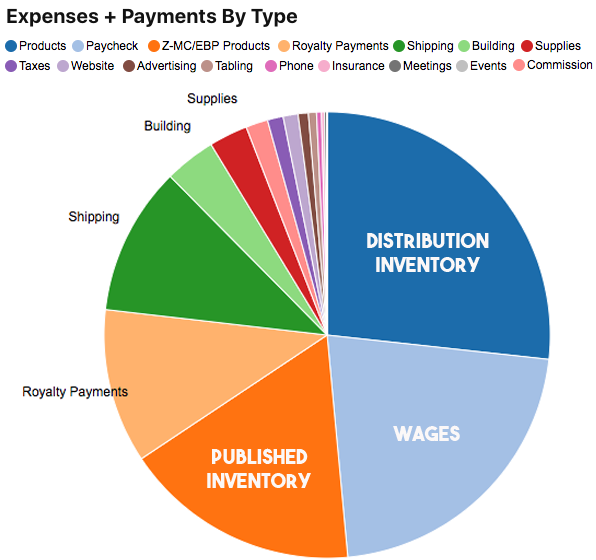

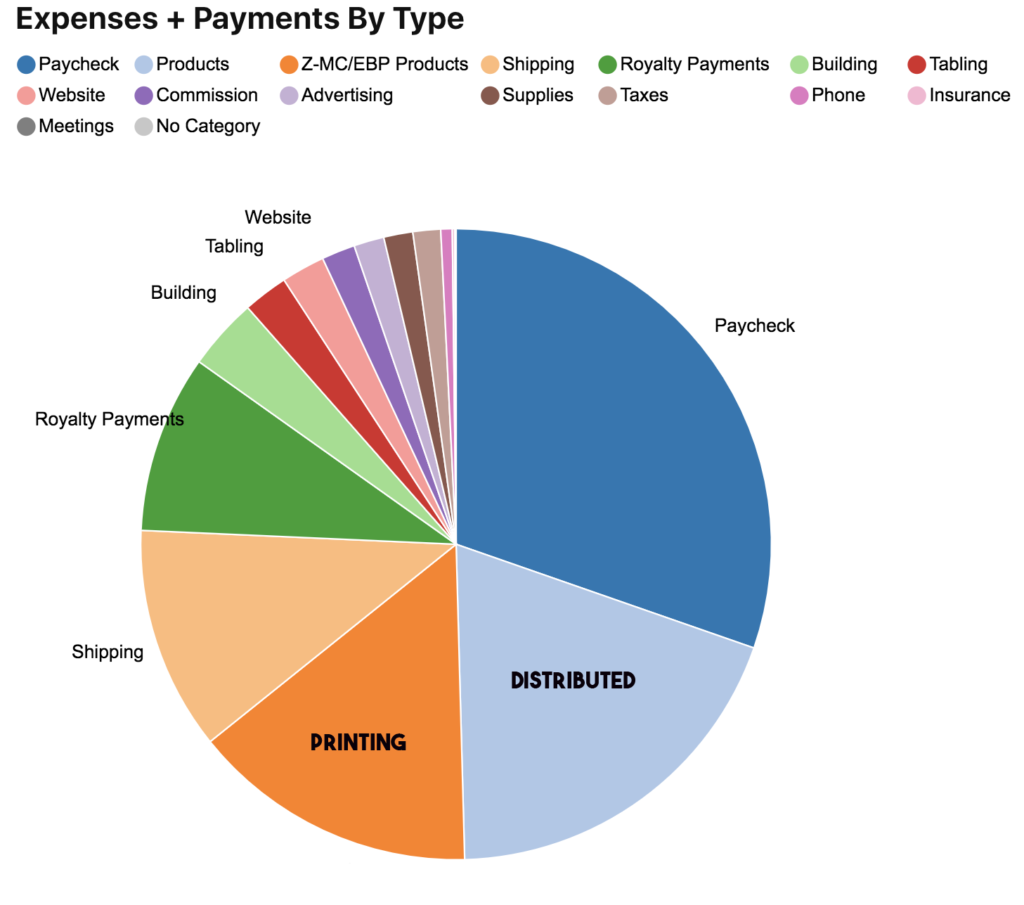

So where did all those millions go? As is written into our company bylaws, we invested it all back into the company and into our workforce, including hiring new workers and those profit-sharing employee bonuses mentioned above. Nobody got a yacht, but we all got by. You can see that piece of the pie alongside the rest of our outgoing money below.

Expenses for this year were $3.8M, which notably includes the self-financing of our continued growth (as opposed to, say, a bank loan):

As you can see, our biggest expense is increasing inventory to fill those warehouses, followed by payroll, the new warehouse we purchased, and shipping.

What trends are we seeing in our patterns? Tarot books were up 40%, Science was up 12%, Spirituality was up a whopping 91%, Humor was up 2.78%, Labor was up 96.78%, Astrology was up 40%, Crystals were up 25%, Anarchism was up 14%, Self-care was up 11%, children’s was up 14%, and Metaphysical was up 2534%!

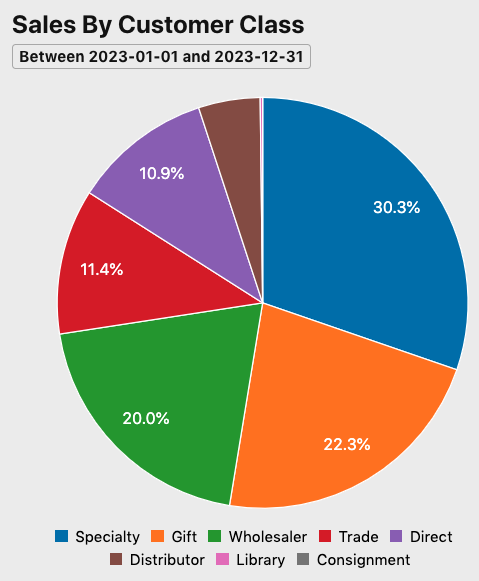

Where are we selling our books? Funny you should ask:

We are back to being mostly sold in specialty stores. Bookstores now comprise about 11% of our sales, about the same as stores and charming individuals who order directly from us. Gift stores took a hit this year, mostly due to underordering. But wholesalers have been increasing. Distributor represents our export sales.

Remember: when you order directly on our website, the author’s royalties are doubled and everything left over goes into profit sharing for our entire staff!

Thank you for supporting us, our authors, and our team in the last year, whether as a reader, partner, or member of our team. The last four years have been difficult in myriad ways, but it’s been heartening the way our entire culture seems to have turned to books for comfort, meaning, perspective, and a little bit of escape. We’re prouder than ever to get to play a role in bringing people and books together.

Tags: annual report, books, business, business of publishing, microcosm publishing

Wow! This year, Microcosm was Publishers Weekly’s fastest growing publisher, based on our growth of 207% between 2019 and 2021 (check out our annual reports for 2019, 2020, and 2021 for more on that wild ride)! Then in 2022, we managed to grow a further 21.3% over 2021. Simultaneously, despite this growth we remain financially solvent, currently owing $648k and owed $652k.

We published 41 new books in 2022, with 17 more coming this Spring and 17 more coming this Fall!

We’re excited to resume conventions in a few weeks with PubWest, Winter Institute, and Vegas Market.

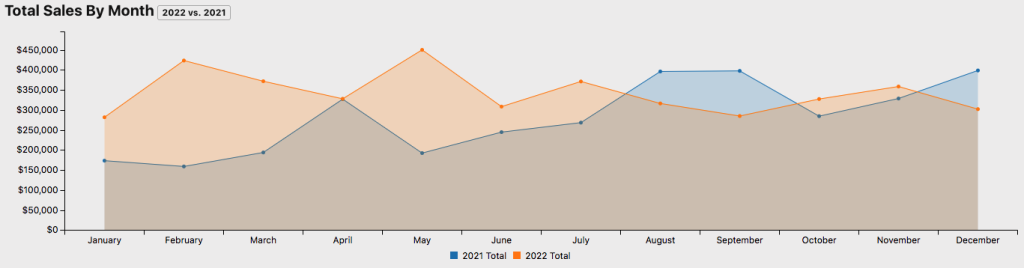

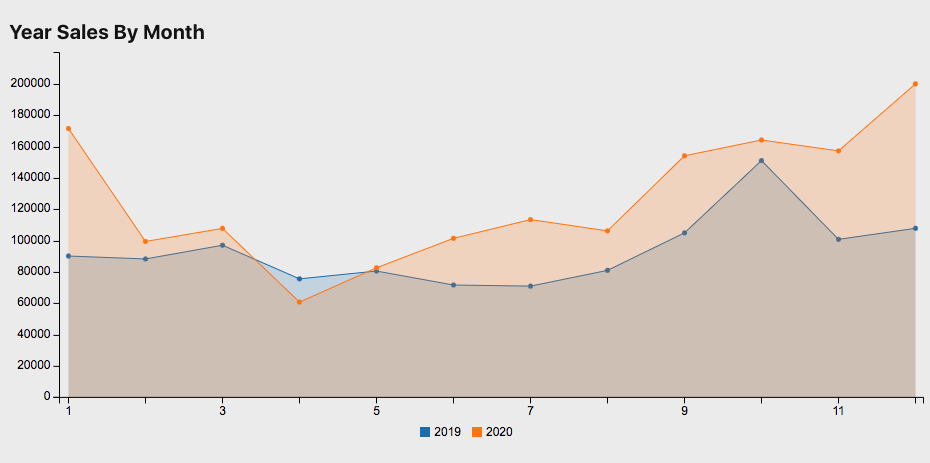

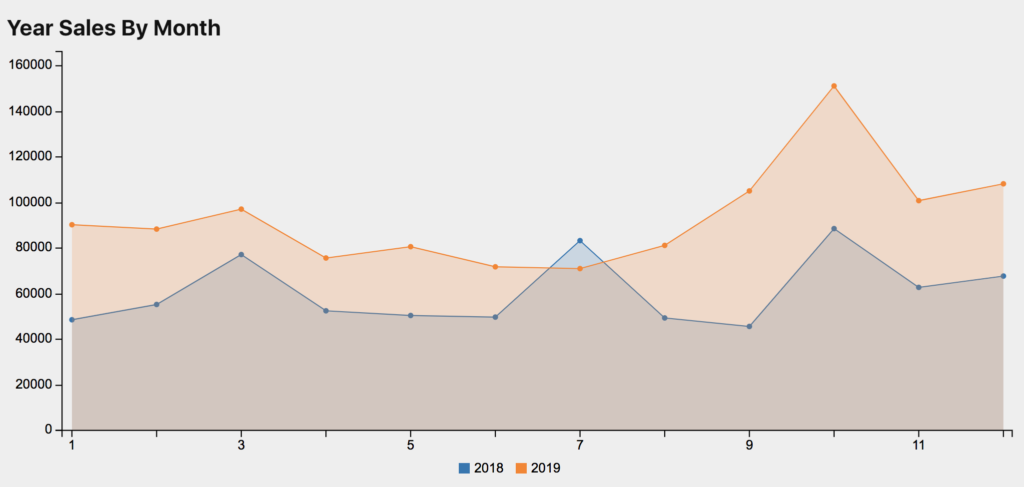

Here’s what the last two years have looked like:

This is another way of saying that we’ve been fighting burnout for three years. We opened an additional warehouse in Cleveland about two years ago, which now handles 67% of our shipments and 78% of our receiving. Our staff has tripled in three years. We are aiming to increase warehouse capacity again later this year, as it is clear that inadequate space is our greatest impediment to growth.

As you can see, the “slow months” for most publishers of January and February can be some of our busiest. And our annual returns are a staggeringly low 2.08%.

Our success continues to be based 50% on what we publish and 50% on how we publish. Meaning that we mostly sell to stores who purchase all of their books from us and so our salespeople don’t stick them with hyped books that they cannot sell. 99% of our books are evergreen, so we aren’t fighting a timer to make them burn bright before they fade away. Best of all, the practical skills and values in our books are what the world has wanted for at least the past 27 years. Probably longer. The need remains vast.

In 2022, we added 2,576 more independent stores that now order from us, bringing the total of retailers that stock our books to over 12,000.

We have seven co-owners, though all profits are shared with our entire staff. In 2022 we were able to increase our budget for wages by 32%, which included a round of profit sharing in December. Because of your support, we are also able to offer health insurance and are instituting further worker benefits in 2023.

The books keep arriving from the printer, just about every day—despite these historic supply chain delays, plus labor and paper shortages at the printers! It continues to be a fascinating time to do what we do. And we are excited that this is finally the year where we will release the beta version of our software to empower other publishers!

And if you really want to get into the nitty gritty of publishing, check out our podcast.

But before we get too tired, let’s take a look at the numbers.

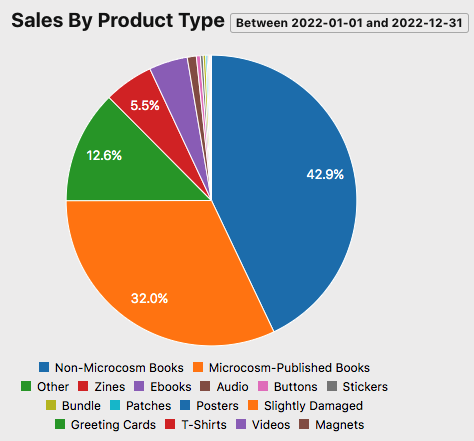

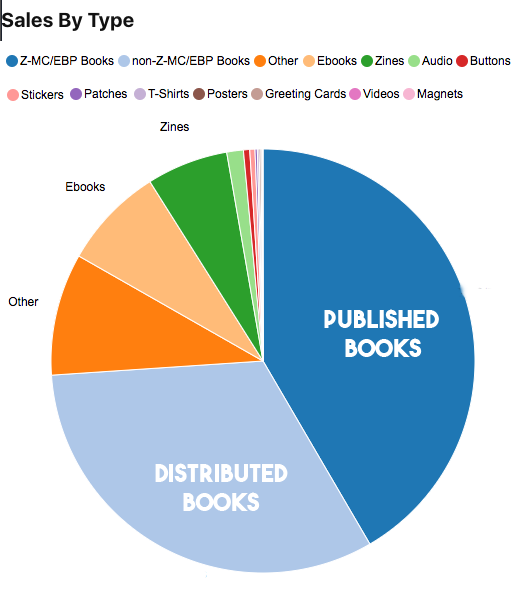

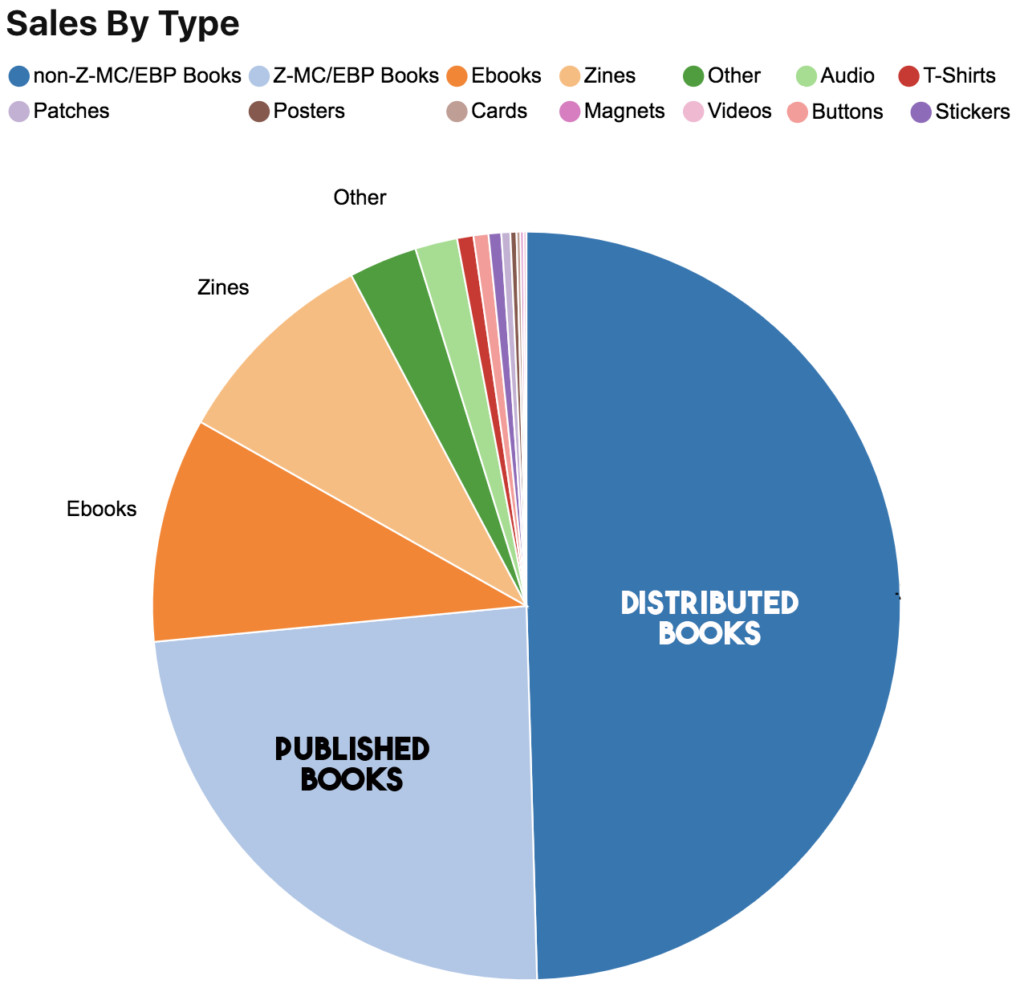

Our total sales for the year were $4.2 MILLION DOLLARS, with our own publishing comprising about 57.1% of our sales:

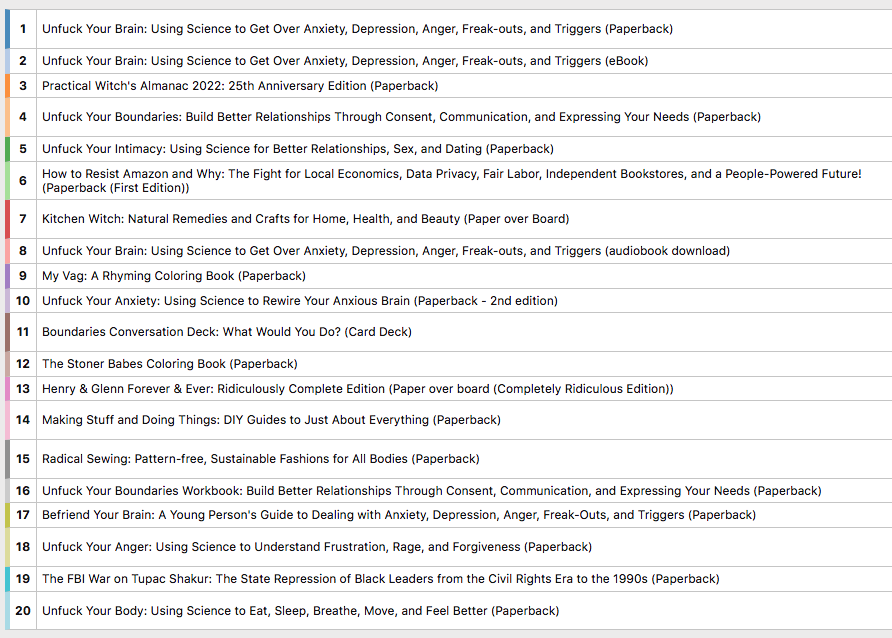

And here are our bestsellers for the year by dollars earned (minus expenses like printing and cover design):

UNF*CK YOUR BRAIN, which we published in 2017, is still outselling the following eighteen (or even 50) books combined by a wide margin—combined. This one title continues to comprise 10.73% of our total sales. Even if you ignore this aberrant title, it was a phenomenal year. We published 41 new books and about twice that many zines. And healthfully, 100% of the titles selling in the top 20 were published prior to 2022, meaning that they will continue to sell for years to come (and we expect our 2022 publications to shine this year).

So where did all those millions go? (We still can’t believe we’re talking about our company sales with all these digits.) As is written into our company bylaws, we invested it all back into the company and into our workforce, including hiring new workers and those profit-sharing employee bonuses mentioned above. Nobody got a yacht, but we all got by. You can see that piece of the pie alongside the rest of our outgoing money below.

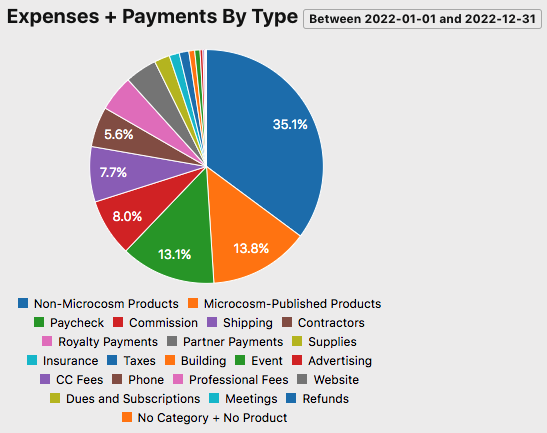

Expenses for this year were $4.2M, which notably includes the self-financing of our continued growth (as opposed to, say, a bank loan):

As you can see, our biggest expense is increasing inventory to fill those warehouses, followed by payroll and sales commissions.

What trends are we seeing in our patterns? What kinds of books are popular for us? Here’s a breakdown, descending by dollars, in terms of changes in sales by subject over 2021:

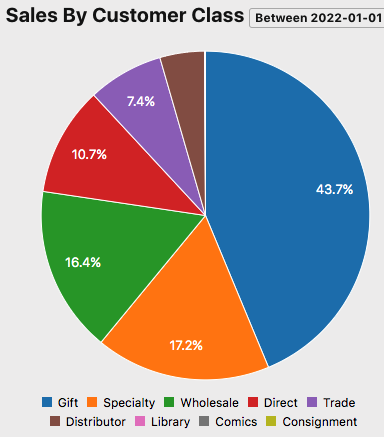

Where are we selling our books? Funny you should ask:

We are now mostly sold in gift shops, a major change from being primarily sold in specialty stores over the past 25 years. Bookstores now comprise about 11% of our sales, about the same as stores and charming individuals who order directly from us.

Remember: when you order directly on our website, the author’s royalties are doubled and everything left over goes into profit sharing for our entire staff!

Thank you for supporting us, our authors, and our team in the last year, whether as a reader, partner, or member of our team. The last three years have been difficult in myriad ways, but it’s been heartening the way our entire culture seems to have turned to books for comfort, meaning, perspective, and a little bit of escape. We’re prouder than ever to get to play a role in bringing people and books together.

Wow! This marks the end of a year of more than doubling our previous “busiest year ever” with a growth of 119.24% over 2020.

At the end of the year, we planned a week of quiet respite. But instead, after holding our breath for a year, omicron hit, coinciding perfectly with a large part of staff going on vacation to cut us down to a rather stressed skeleton crew. But now we’re resting up, reflecting on the last year, and planning for the year to come. And that includes publishing our annual financial and business recap! Financial transparency is one of our values—it helps everyone! And this year, it’s extra nice to be able to show that all the news is good.

In February, 2021, we doubled our warehousing space (and shortly after that our warehouse staffing) with the opening of our Cleveland warehouse. And still, we struggled to keep up with shipping and receiving at the end of the year. Similarly, we had many system and software upgrades and we still couldn’t keep up with our new volume of orders and books. So naturally, we decided to keep it going by publishing 19 new books in the Spring 2022 season, and 23 new books next Fall. National conventions resume in a few weeks and lots of authors are submitting finished books that need attention, but maybe we can run a broom through here in the meantime and clear out the 2021 dust.

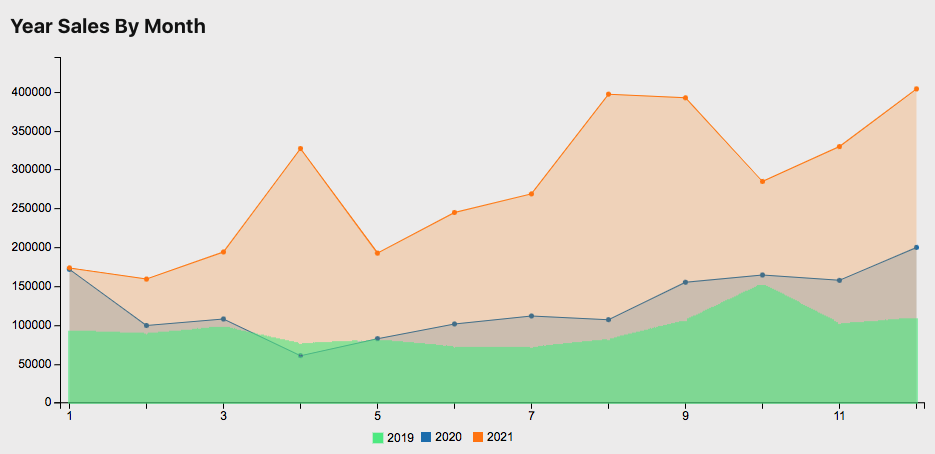

Here’s what the last 3 years have looked like:

[IMAGE DESCRIPTION: a graph showing three years of income by month superimposed on each other: 2019 is the lowest, with the best month hitting $150,000. 2020 had somewhat higher sales almost every month, ranging from about $70k to $200k. And 2021 looks like a mountain range by comparison, with sales hitting $400k several times.]

When other publishers ask how we have been doing and I explain the above chart, their eyes light up in shock and they respond with something like “Well, that’s a GOOD problem!” Which it is, but it’s the kind of problem that resulted in six years without a slow season. For most publishers, January and February are marked by an inundation of returned, unsold books from the holiday season, while we receive restock orders instead. The reasons for this are 50% what we publish and 50% how we publish. Meaning that we mostly sell to stores who purchase all of their books from us and so our salespeople don’t stick them with hyped books that they cannot sell. And we can confirm that the practical skills and values in our books are what the world has wanted for at least the past 26 years. Probably longer. The need remains vast.

We have more than doubled our staff since before the pandemic and we welcomed Sarah as our seventh employee-owner in 2021. Thanks to your support, we were able to give our exhausted staff their largest rounds of profit bonuses ever—equivalent to a $3/hour raise for the last year. Our latest rounds of hiring have been a little too steady to continue to report each new worker, but we have gotten our about page mostly updated other than the three newest and a few people who have been here for ten years but haven’t sent a photo! Our newfound health insurance has been providing people with long-neglected (and sometimes life-altering) care. And we are ready to debut our software to allow other publishers to do what we do! Yet, the books keep arriving from the printer, just about every day—after these historic supply chain delays! It’s been a fascinating time to do what we do. And we are excited that this is finally the year where we will release the beta version of our software to empower other publishers!

And if you really want to get into the nitty gritty of publishing, check out our podcast.

But before we get too tired, let’s take a look at the numbers.

Our total sales for the year were $3.449 MILLION DOLLARS, with published books taking the largest slice of that pie, and finally exceeding distribution sales of the past few years:

And here are our bestsellers, by dollars earned (minus expenses like printing and cover design):

| Title | ISBN | Quantity | Total | Retail | Wholesale | Distributor | Web Qty | Profit/Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfuck Your Brain: Using Science to Get Over Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Freak-outs, and Triggers (Paperback) | 9781621063049 | 42,167 | $281,504.84 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 1316 | +4656.99 / month |

| Unfuck Your Brain: Using Science to Get Over Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Freak-outs, and Triggers (eBook) | 9781621060406 | 53,280 | $63,994.34 | 13.99 | 8.39 | Z-MC-VERSA | 6773 | +3208.21 / month |

| Unfuck Your Boundaries: Build Better Relationships through Consent, Communication, and Expressing Your Needs (Paperback) | 9781621061007 | 7,415 | $50,997.34 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 284 | +3.91 / month |

| Practical Witch’s Almanac 2021, The (Paperback) | 9781621066552 | 7,915 | $49,618.54 | 13.95 | 8.37 | Z-MC-VERSA | 588 | +503.40 / month |

| How to Resist Amazon and Why: The Fight for Local Economics, Data Privacy, Fair Labor, Independent Bookstores, and a People-Powered Future! (First Edition Paperback) | 9781621067061 | 7,711 | $46,992.21 | 12.95 | 7.77 | Z-MC-VERSA | 0 | +1.97 / month |

| Gold Lyre Tarot (Deck) | 9781621067870 | 2,748 | $43,592.54 | 29.95 | 17.97 | Z-MC-RR Donnelly | 52 | +848.86 / month |

| Boundaries Conversation Deck: What Would You Do? (Other) | 9781621063704 | 18,032 | $42,052.35 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-RR Donnelly | 43 | +394.32 / month |

| Unfuck Your Intimacy: Using Science for Better Relationships, Sex, and Dating (Paperback) | 9781621067627 | 5,257 | $37,007.59 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 248 | +886.88 / month |

| Unfuck Your Brain: Using Science to Get Over Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Freak-outs, and Triggers (audiobook download) | 9781621063049 | 246,0621 | $32,777.80 | 19.99 | 11.99 | Z-MC-VERSA | 100 | +486.30 / month |

| Making Stuff and Doing Things: DIY Guides to Just About Everything (Paperback) | 9781621066477 | 3,538 | $26,403.97 | 16.95 | 10.17 | Z-MC-VERSA | 275 | +1138.62 / month |

| Unfuck Your Body: Using Science to Eat, Sleep, Breathe, Move, and Feel Better (Paperback) | 9781621063285 | 3,154 | $23,853.55 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 1592 | +208.77 / month |

| Unfuck Your Boundaries Workbook: Build Better Relationships Through Consent, Communication, and Expressing Your Needs (Paperback) | 9781621061762 | 4,941 | $22,760.48 | 9.95 | 5.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 425 | +232.27 / month |

| Make Your Place: Affordable, Sustainable Nesting Skills (Paperback) | 9780978866563 | 16,048 | $18,487.40 | 9.95 | 5.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 145 | +3084.17 / month |

| Stoner Babes Coloring Book , The (Paperback) | 9781621064305 | 2,367 | $18,019.72 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 72 | +1.83 / month |

| Unfuck Your Brain Workbook: Using Science to Get Over Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Freak-Outs, and Triggers (First Edition Zine ) | 9781621065890 | 7,749 | $16,968.14 | 4.95 | 2.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 384 | +352.38 / month |

| Henry & Glenn Forever & Ever: Completely Ridiculous Edition (Paper over board) | 9781621068402 | 1,379 | $15,831.85 | 25.95 | 15.57 | Z-MC-VERSA | 159 | +437.76 / month |

| Green Witch: Your Complete Guide to the Natural Magic of Herbs, Flowers, Essential Oils, and More, The (Hardcover) | 9781507204719 | 1,424 | $15,321.05 | 17.99 | 10.79 | 10 | +0.96 / month | |

| My Vag: A Rhyming Coloring Book (Paperback) | 9781621068907 | 2,024 | $15,201.91 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 37 | +1.00 / month |

| Unfuck Your Boundaries: Build Better Relationships through Consent, Communication, and Expressing Your Needs (Ebook) | 9781621060673 | 36,814 | $14,615.26 | 9.99 | 5.99 | Z-MC-VERSA | 178 | +700.09 / month |

| Make Your Place: Affordable, Sustainable Nesting Skills (Paper-over-board) | 9781621061250 | 1,941 | $14,500.00 | 14.95 | 8.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 1412 | +252.48 / month |

| You Are a Great and Powerful Wizard: Self-Care Magic for Modern Mortals (Paper over boards) | 9781621064831 | 1,599 | $14,483.33 | 19.95 | 11.97 | Z-MC-VERSA | 0 | +0.93 / month |

UNF*CK YOUR BRAIN, which we published in 2017, is still outselling even our runners up by a wide margin—combined. Even if you ignore this aberrant title, it was a phenomenal year. We published 42-some new books and about twice that many zines. And healthfully, 87% of the titles holding sales are over a year old, meaning that they will continue to sell for years to come.

So where did all those millions go? (We still can’t believe we’re talking about our company sales with all these digits.) As is written into our company bylaws, we invested it all back into the company and into our workforce, much of it in the form of those profit-sharing employee bonuses mentioned above. Nobody got a yacht, but we all got by. You can see that piece of the pie alongside the rest of our outgoing money below.

Expenses for this year were $3.346M, including the purchase of the additional warehouse and inventory to fill it:

Thank you for supporting us, our authors, and our team in the last year, whether as a reader, partner, or member of our team. The last two years have been difficult in many ways, but it’s been heartening the way our entire culture seems to have turned to books for comfort, meaning, perspective, and a little bit of escape. We’re prouder than ever to get to play a role in bringing people and books together.

Yikes! 2020 was one of those years that most simply feel lucky to hobble out of. At the beginning of the pandemic this spring, we expected the worst, but calculated that even if sales slowed to a halt, we could keep the company afloat for six months without layoffs or pay cuts. But it turned out that we had the opposite concern: we are selling twice as many books out of our warehouse as we were two years ago, and our staff has grown by six additional people this year, to a total of 17. These are good problems to have, but like so many people this year, we’re emotionally exhausted by all that’s happened this year … and we still can’t keep up with shipping orders.

Unbelievably, our 2020 sales went up 64% over 2019, making 2020, again, our best year ever! In the past year we’ve also increased staff wages by an additional 33% and an average raise of 8.04% per person , with another 33% bonus in December! We are welcoming our sixth employee owner this year as well with a seventh on the way. Despite considerable personal difficulties and losses, everyone on our team has shown up with consistency and deep care for their work. It’s been a relief and a privilege to be able to provide a safe port for our workers in the storms of 2020, and for the next year we are looking at ways to create even more lasting stability while continuing to expand the team.

We’ve again long outgrown our office and warehouse and are now returning to our roots. In March we’ll be opening and operating an additional warehouse in Cleveland. Soon we will welcome Drew, who helped out at Microcosm in the 90s, to manage the new location. Now that Microcosm is a veritable adult, it seems only appropriate that it can also become a full time job.

Aside from more space, social distancing, and people power, the additional warehouse will help us to ship more efficiently to the midwest and east coast U.S. This should help us to get our work to nearby stores much faster and try to keep pace with how much things are picking up. We’ve also added additional field sales reps in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, South Dakota, North Dakota, Illinois, and New Jersey. It’s truly incredible to watch our work end up in more and more stores. Returning to independent distribution at the beginning of 2019 was truly the best decision we ever made, and is a huge part of why we made it through 2020 in such good shape (though, again, exhausting).

Let’s look at the numbers.

Our total sales for the year were $1.67 million dollars. Here’s what we are selling. As you can see, zines jumped past ebooks while most of the rest held consistent with 2019 percentages, though published books began gaining on distributed in the latter portion of the year:

Here are our bestsellers, by dollars:

Note that Unf*ck Your Brain, which came out in 2016, is still outselling our other top 20 books, combined. If you disregard the curve breaker, it was a strong year. We published 25 books last year (not including half a dozen that were delayed until 2021), and not all of these new releases immediately took off—only 6 of our top 20 sellers for the year actually came out in 2020—but our backlist absolutely thrived. For instance, Making Stuff & Doing Things, clocking in at #5 for the year, first came out in 2002.

Expenses this year were $1.669M, because of the ongoing increased costs of growth and staff raises. The major shifts this year were our greatest expense went from being salaries to distributed inventory (due to increased managed levels from regular weekly sales), and we now spend more on royalties than on shipping:

One expense that is not in our budget is office snacks! Several zine authors for the last year or more have asked us to direct their royalties into taking care of our workers, and as a result we are able to keep a good supply of snacks and beverages on hand to fuel both blood sugar and morale for the folks who are still needing to work on-site. Thank you, charming benefactors!

To our readers, partners, and teammates: We always appreciate your orders, trust, and contributions, and recognize it’s been a difficult year so your support makes all the difference. Your support has helped us to support our staff, pay royalties to our authors, pay our bills on time, continue to donate books to community programs and send books to people in prison, and do our best to keep our corner of the publishing and bookselling ecosystem afloat. Let’s still hope that 2021 is a little bit easier.

If you want to learn more about publishing, check out new episodes of our weekly pod/videocast if you want to listen to two nerds dissect publishing!

And a friendly reminder: While we’re legally a “for-profit” organization, we choose to operate on a break-even basis. This means that when we have profits, they don’t go into perks for our owners; they go into staff wages and taking a chance on publishing new books we believe in. Getting to do work we care about every day and put books out there that help people change their lives is the best kind of perk.

There’s no way around it: our first year returning to self-distributing was an incredible success!

Unbelievably, our 2019 sales went up 55.77% over 2018, making 2019, again, our best year ever! In the past year we’ve also increased staff wages by 38.94%, with more to come!

At the same time, 2019 really taxed and tested us in ways that we haven’t seen before. We are shipping an average of six times as many packages every day as we were when we moved into this building eight years ago. We are receiving six times as many boxes every day as well. All of this leads to the increased need for diligence and refinement as we outgrow old systems.

Sure, everyone works harder as well and it’s nice to have that acknowledged. 2019 also saw the implementation of the employee ownership program and we now have five owners with more on the way. We also switched our podcast from quarterly to weekly and added a vlogcast version.

As the growth seems constant and endless, we have to stop and ask bigger long-term questions: when will we need to hire another staff person (February?)? When will we give the next round of raises (April!)? These are wonderful problems to discuss and the opposite of our situation eight years ago when the current staff took over the company.

We are publishing more books than ever (and reprinting more books than ever too!) and most of this year has been spent implementing new systems to use data to make better decisions and where we have the most growth opportunities.

Most important is the constant feedback we receive from our work. We’ve expanded our books to prisoners program as well this year and many people write back, shocked that we responded at all—let alone sent me them a pile of books to read. Seeing readers recommend our books on social media has been flattering but nothing holds a candle to someone spilling their guts about how much they were singularly impacted in a private letter.

Let’s look at the numbers.

Our total sales for the year were $1.273 million dollars. Here’s what we are selling:

Here are our bestsellers, by dollars:

Expenses this year were also right at $1.27M, partially due to the 38.94% staff raises:

And the real shocker, comparing 2019 to 2018:

And a friendly reminder: While we’re legally a “for-profit” organization, we choose to operate on a break-even basis. This means that when we have profits (which isn’t all the time, but we try), they don’t go into our owners’ yacht fund; they go into staff wages and taking a chance on publishing new books we believe in. Getting to do work we care about every day and put books out there that help people change their lives is way better than a yacht. Which is an important attitude to have in the publishing industry!

This week on the People’s Guide to Publishing vlogcast, Elly and Joe compare fiction to nonfiction and see if the claim that marketing fiction is different from marketing nonfiction holds up!

Thank you for watching the People’s Guide to Publishing vlogcast!

Get the book: https://microcosmpublishing.com/catalog/books/3663

Get the workbook: https://microcosmpublishing.com/catalog/zines/10031

More from Microcosm: http://microcosmpublishing.com

More by Joe Biel: http://joebiel.net

More by Elly Blue: http://takingthelane.com

Subscribe to our monthly email newsletter: https://confirmsubscription.com/h/r/0EABB2040D281C9C

Find us on social media

Facebook: http://facebook.com/microcosmpublishing

Twitter: http://twitter.com/microcosmmm

Instagram: http://instagram.com/microcosm_pub

Back in February, Portland’s had big snow scare…the same night as Dr. Faith Harper’s event at Powell’s Books for Unfuck Your Intimacy + Coping Skills. She answered TONS of audience questions.