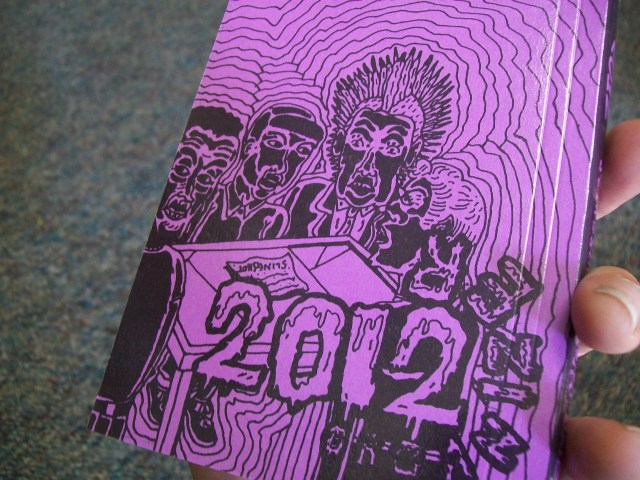

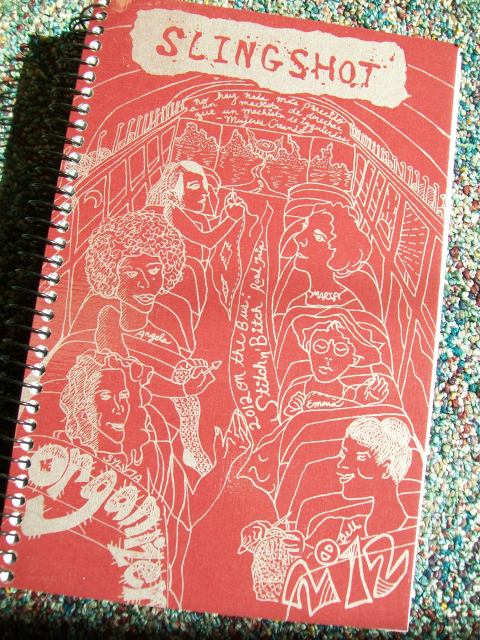

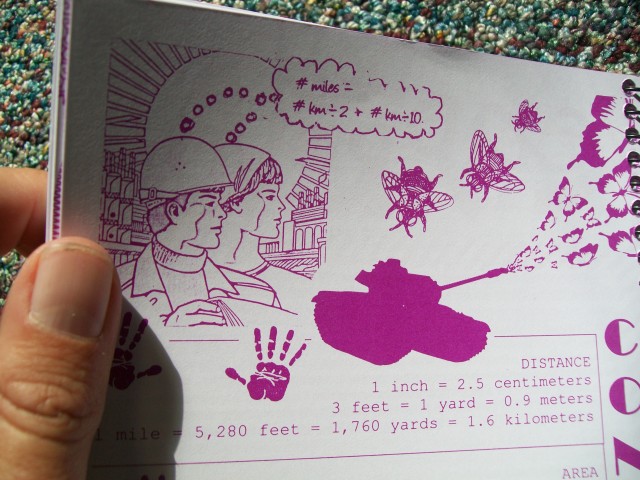

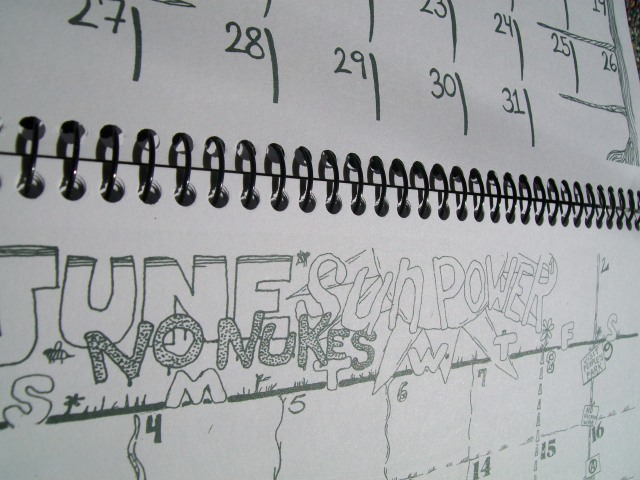

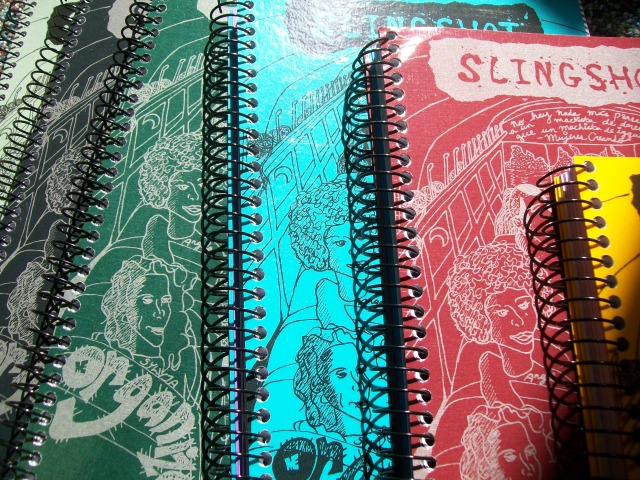

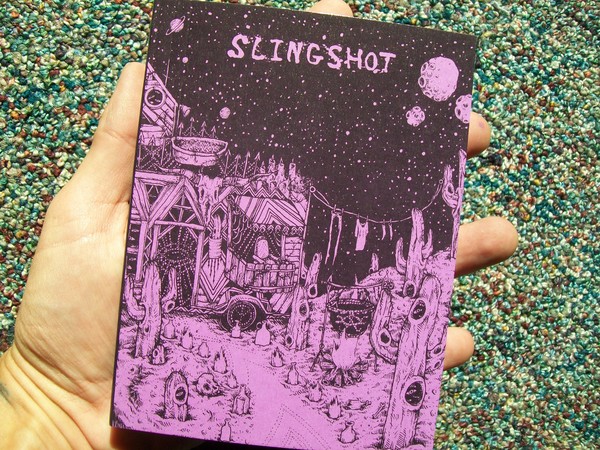

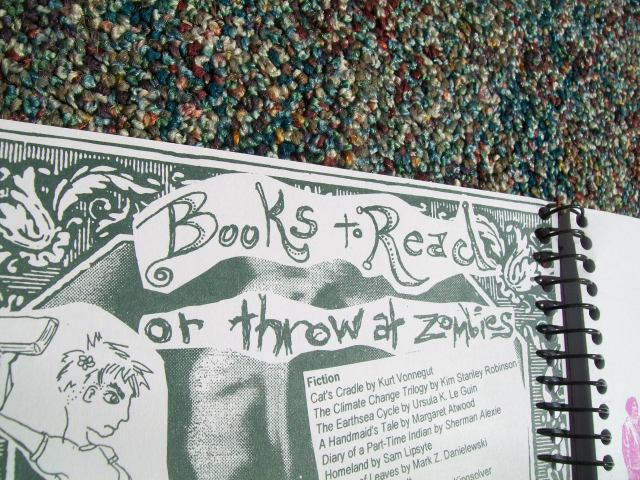

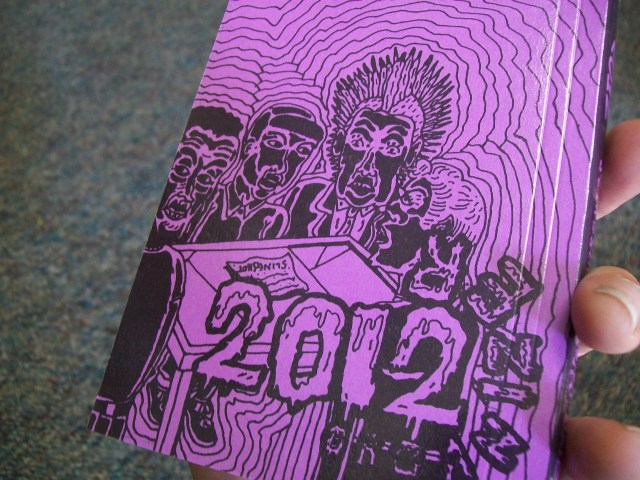

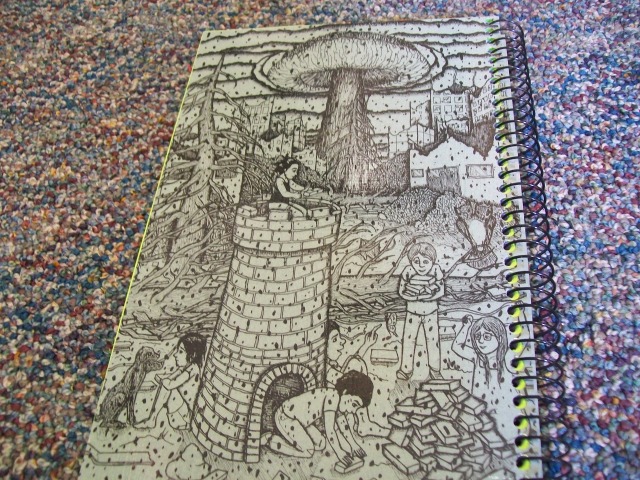

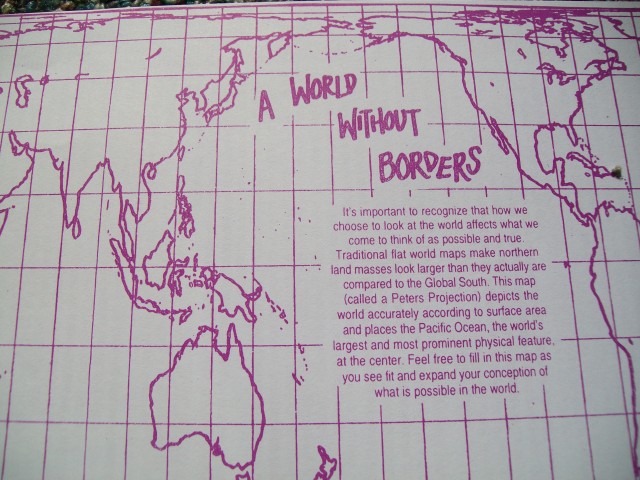

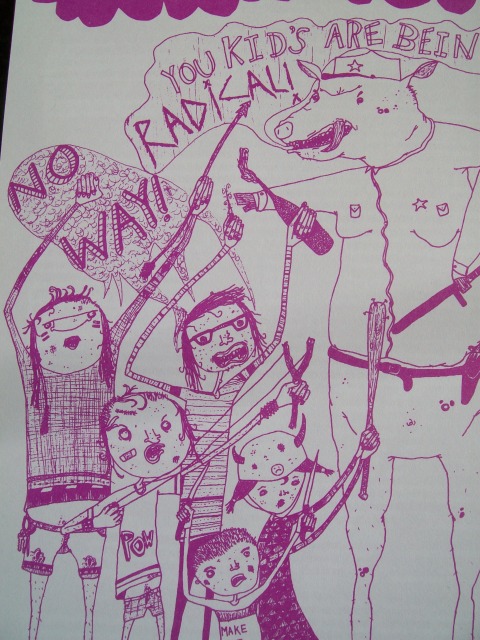

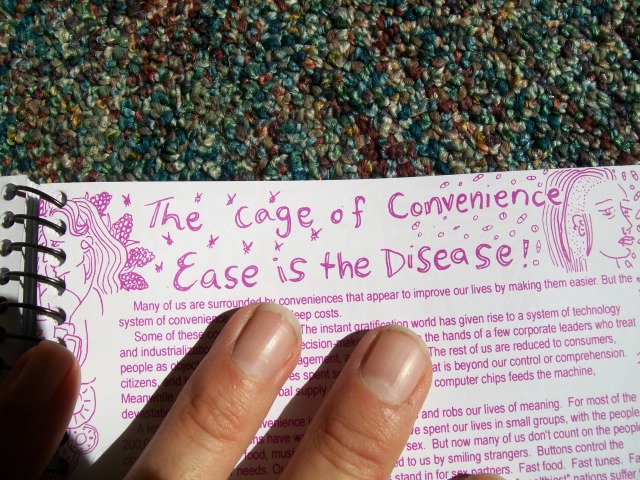

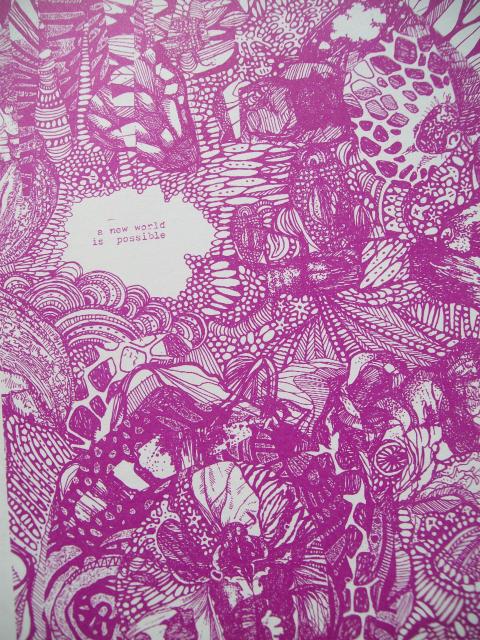

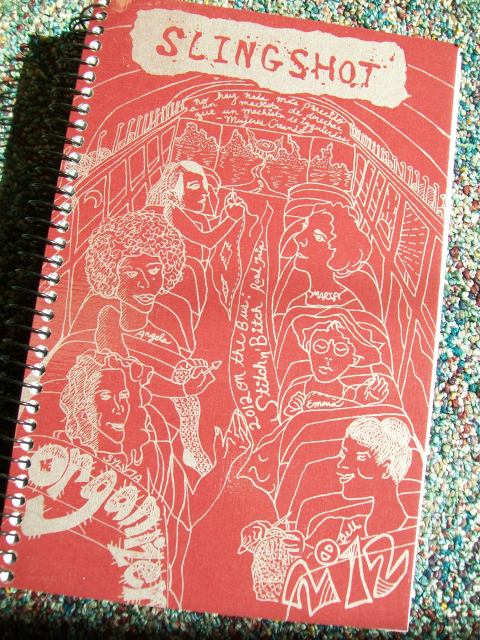

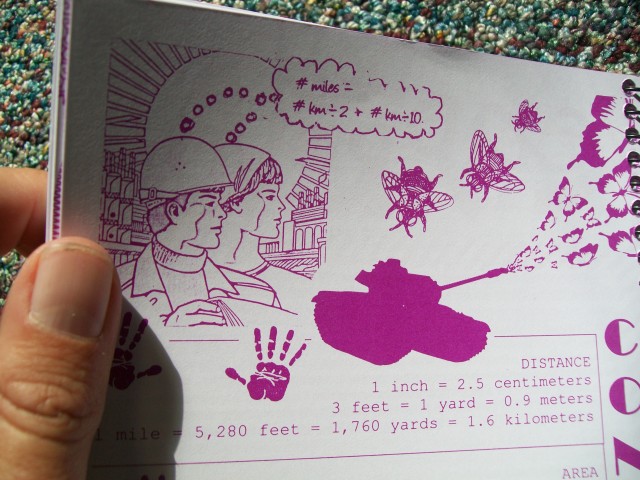

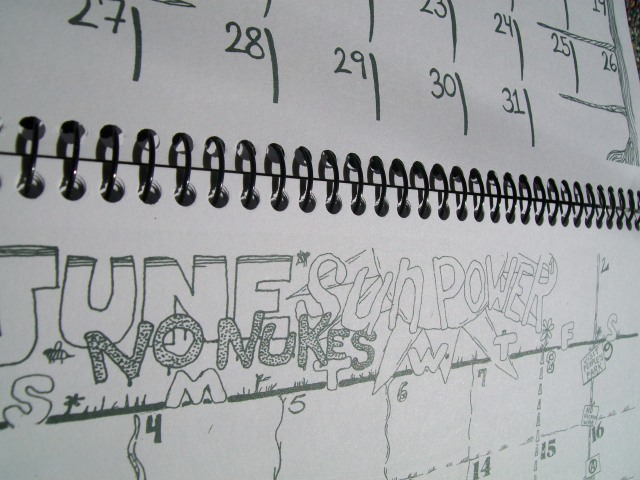

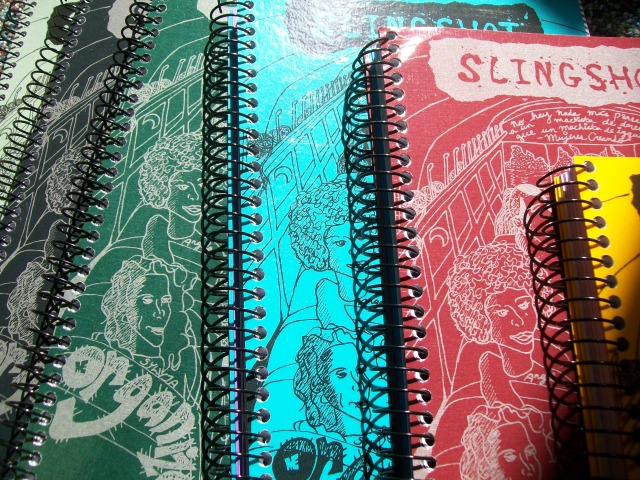

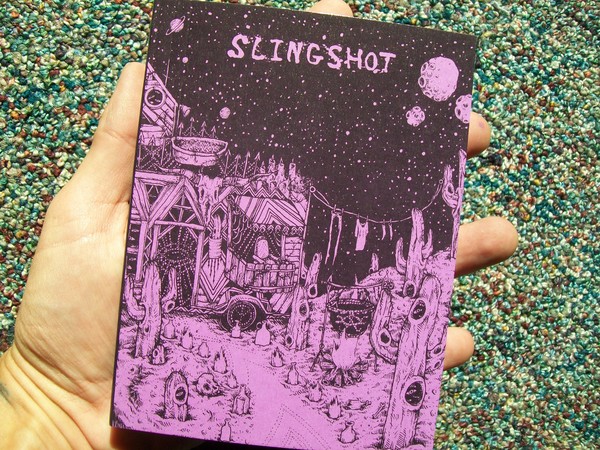

Featured Awesome Product of the Week! Slingshot Planner 2012! Photo Gallery! A First Look!

They’re out now! Yes! We have them! So exciting! Featured Awesome Product of the Week! Go here to order. See below for an inside look!

They’re out now! Yes! We have them! So exciting! Featured Awesome Product of the Week! Go here to order. See below for an inside look!

Do you sometimes feel angry, powerless, or in need of a pick-me-up? Want to connect to a range of movements seeking to define, establish, and defend rights for women? Whether you want gender theory, battles for equality, campaign against violence, harassment, and assault, the social construct of gender, the real experiences of women, and the battles for reproductive rights, this is a good place to start or continue. The first-person voice of zines can empower you or just brighten your day!

This pack generally includes: Dog Dayz, Emergency, Figure 8, Hatch Mister Sister, I Choose My Choice, It’s Not Just Boys Fun, The La La Theory, Miranda, Tear Valve, Thoughts About Community Support, and five Bad Habits postcards.

If we’re out of something, we’ll substitute from these: Ask First, Learning Good Consent, Green Zine #14, Hot Pants, Take Back Your Life, Support, Taking the Lane, and Womanifesto for the Catagorical New Freedom Lady!

Missed the DINNER + BIKES tour? Check out this video!

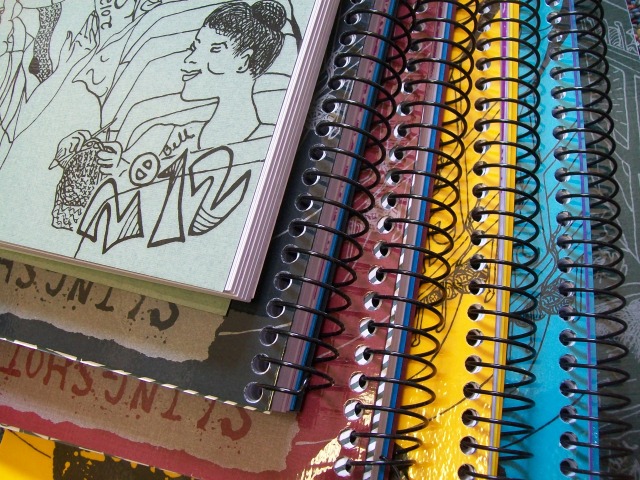

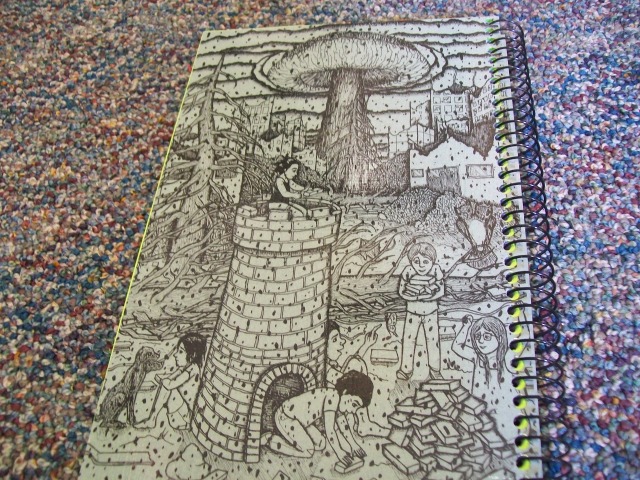

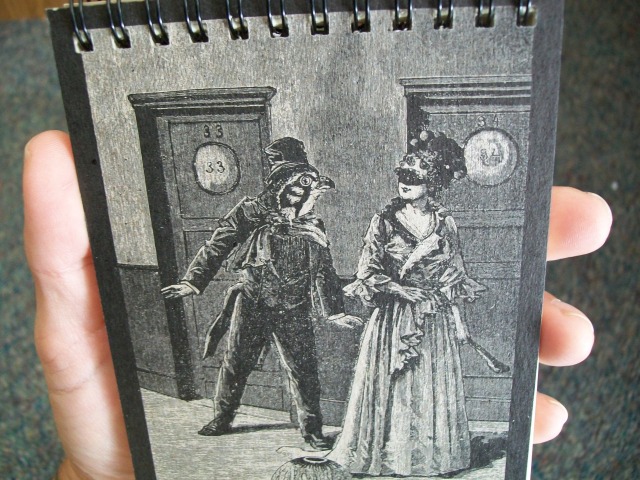

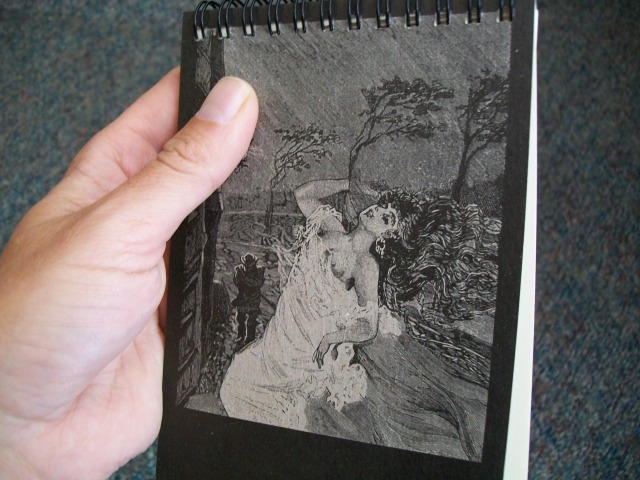

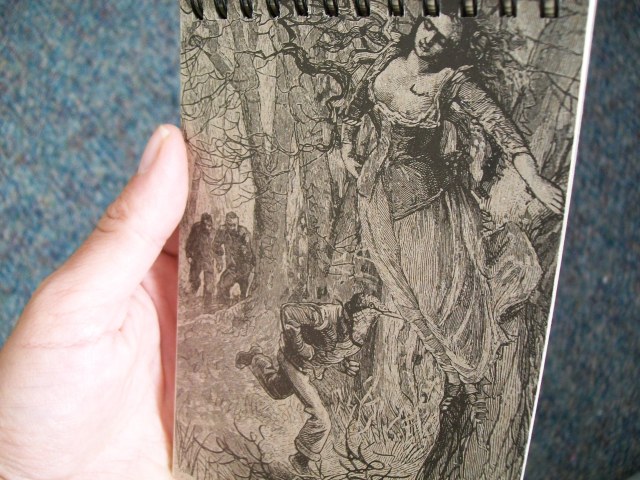

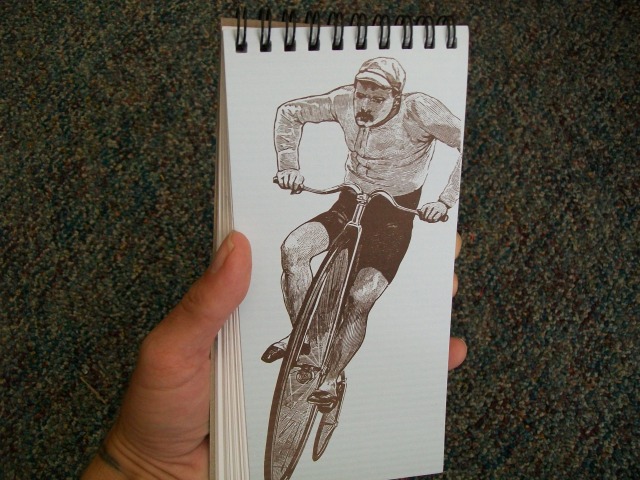

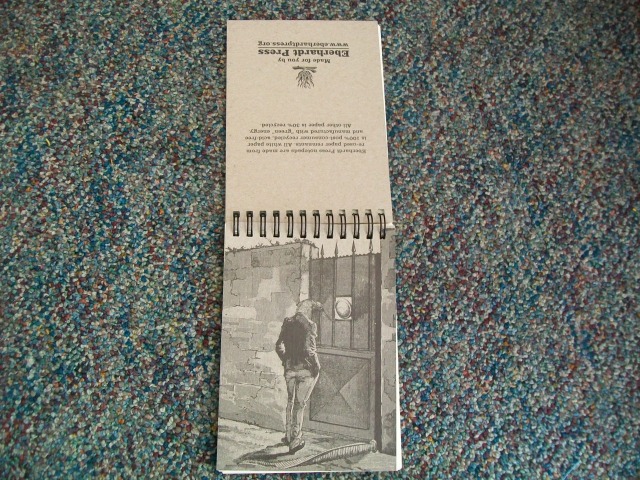

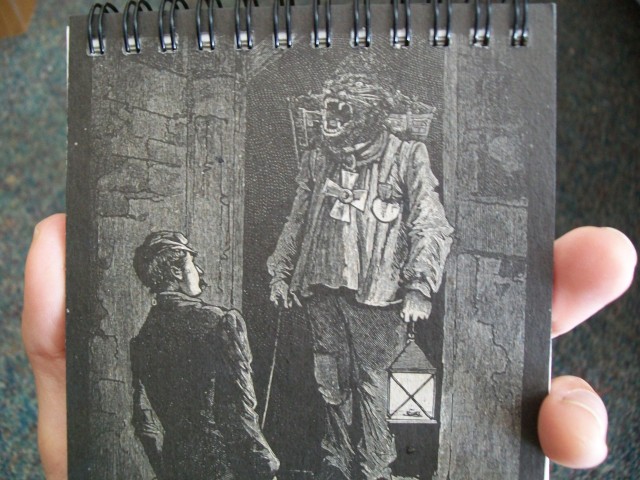

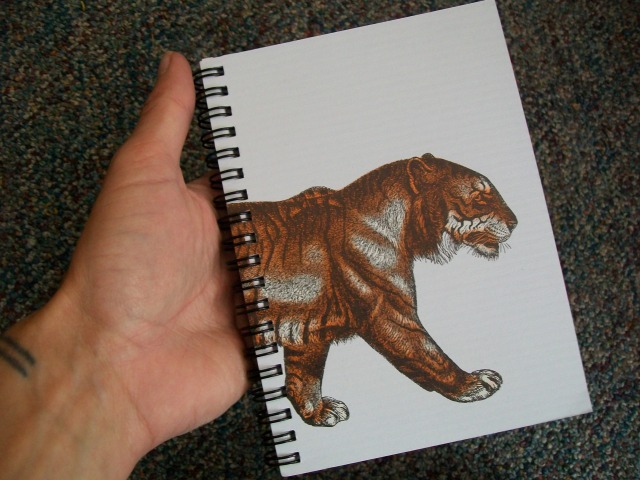

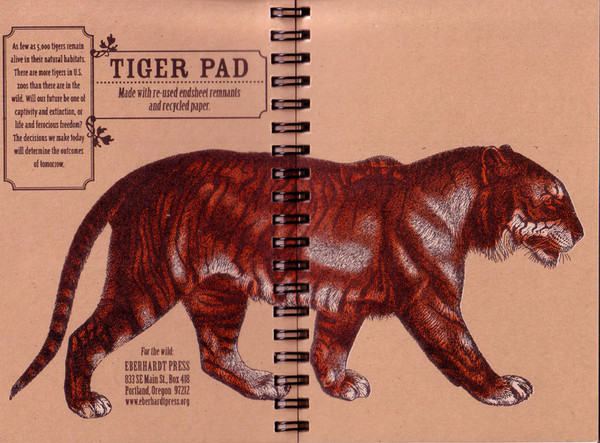

For the final part of our celebration of the massively awesome Eberhardt Press, we present our “Featured Awesome Product of the Week” (the first installment of a new weekly blog series here at the Microcosm blogifesto.) This week it’s Eberhardt’s blank notebook/journal series. They’re available in a bunch of different sizes and designs, five of which feature the art of surrealist Max Ernst and two more (two colors, blue and orange) feature a gorgeous lookin’ tiger. We’ve only got a small amount of these beauties so get ’em while they’re hot. (For more info on Eberhardt read an interview we did with Ebehardt’s Charles right here.)

If you’re looking for someone awesome and dependable to print your zine or book you should totally check out Eberhardt Press. Charles from Eberhardt does all our zine printing and the guy’s work is always solid. We chatted up Charles and got the scoop on what he does…

Q: For folks unfamiliar with Eberhardt, tell us what kind of services you offer…

Q: What is your advice for someone who wants, say, 500 to 1000 copies of their zines and has a bit of money to have it printed?

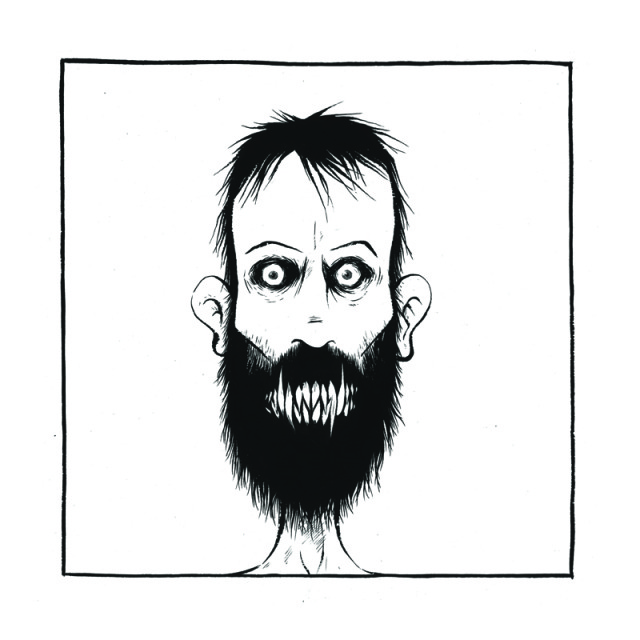

Q: What is your advice for someone who wants, say, 500 to 1000 copies of their zines and has a bit of money to have it printed?Last week we chatted up Henry and Glenn Forever‘s Tom Neely about his awesome new book, The Wolf! Here are the results! The book is somethin’ special, so make sure to check out those awesome illustrations at the end!

Q: For people who haven’t gotten a chance to check out the new book, tell ’em a bit about what they can expect…

A: I’m never very good at describing my art, but here goes: It’s a surrealistic story told through a narrative series of paintings that pull you through a psychedelic nightmare of werewolves and skeletons and forests and sex and… it’s also a love story.

Q: This book is vastly different from Henry and Glenn Forever, do you think the people you liked HG will be into it?

A: Some of them might. I don’t expect everyone to like everything I do. It’s about as different from Henry and Glenn as you can get, but it would be cool if some of the people who love Henry and Glenn would give The Wolf and some of my other art a chance. The art-comix fans and the metal-heads who read my stuff seem to be latching onto it. It’s more of a serious, arty, poetic piece, whereas Henry and Glenn Forever is just random and funny, but if you like werewolves and sex and scary skeletons and symbolism and surreal art, then you might be into it.

Q: You’ve been working on The Wolf for three years. How did it originally come about?

A: It started as a series of semi-pornographic werewolf paintings I did for a solo gallery show back in 2007. From there, the ideas for the characters and story kept evolving over time. This book took longer than my others because the process was more improvisational and always in flux. Ideas were always changing and taking me in new directions. I wanted the whole book to evolve as I went along. I didn’t know if it would ever end, but it finally finished itself.

Q: What’s next? What sorts of projects do you have under your belt?

A: Oh, too many things… I’ve always got more ideas than time. I’m working on a few short comic stories for some anthologies. My next graphic novel is already written, but I don’t know when I’ll start drawing it. I’m working on some paintings and other art projects… and what everyone really wants to hear—yes, we are working on more Henry and Glenn stuff.

Order Tom Neely’s The Wolf here. http://www.iwilldestroyyou.com/store.html

Here’s a recap of 1% of what went on at Minot’s Why Not? Festival.

If you are interested in holding a benefit show to raise money for supplies for the DIY punx who are doing volunteer restoration work on homes during an extreme housing crisis, contact <a href=”billyluetzen@yahoo.com”>Billy</a>.

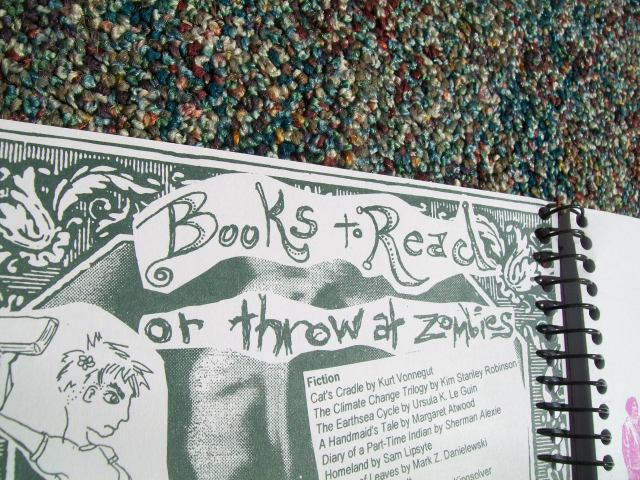

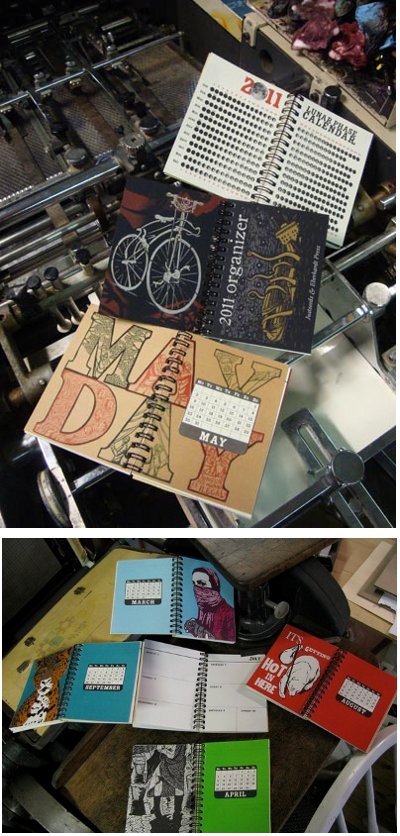

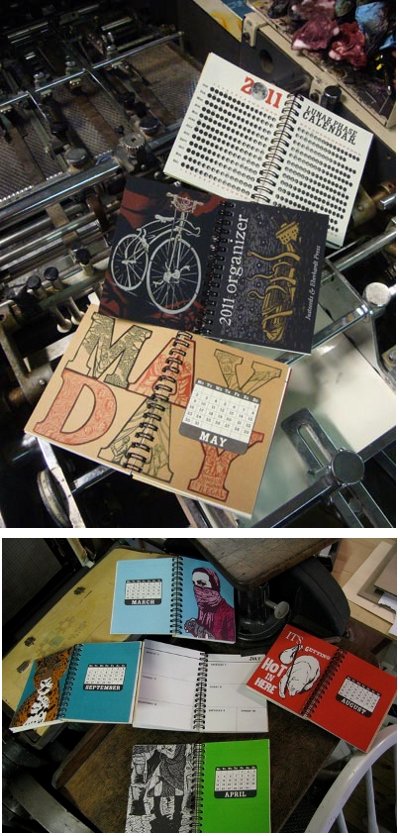

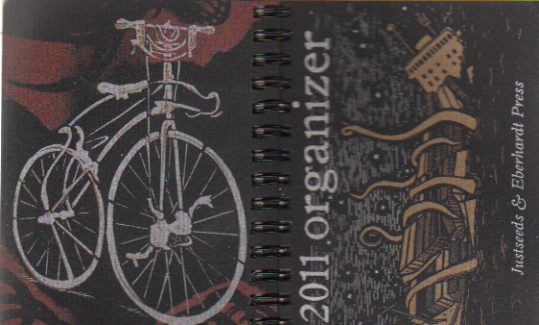

The good folks behind Eberhardt Press and Just Seeds have teamed up to create an awwwwesome 2011 day planner (think Slingshot.) These lil’ puppies are beeeautiful and feature 14 Just Seeds artists, including Icky A., Shaun Slifer, Erik Ruin, Josh MacPhee, and Kristine Virsis! The design, by Charles Overbeck, is elegant and tasteful, and features curatorial help from Roger Peet. In the back is a lunar phase calendar. Strong wire binding allows it to sit flat on your desk. Thick cardstock protects it in your pocket or your messenger bag. Totally, totally solid.

Right now to celebrate all-things Eberhardt and Just Seeds (stay tuned for an interview with Charles Overbeck and Eberhardt blank notebooks available through this site!) we’re doing a big ol’ planner sale.

Go here to check ’em out and buy ’em for $5 (marked down from $6) or just opt for a between $3-$7 sliding scale option.

These organizers are a special thing. We hope you get as stoked about them as we are!

Love,

Microcosm

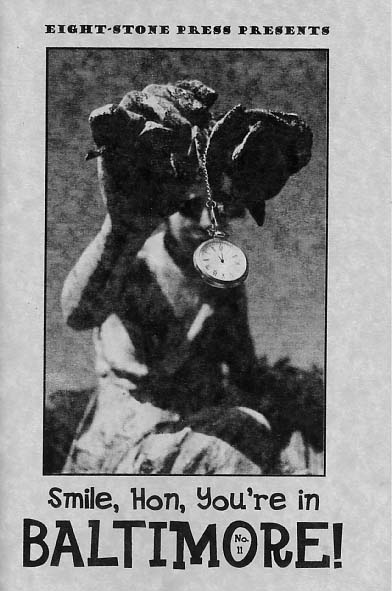

Hey Baltimore friends!

Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore editor William P. Tandy is hosting an event tomorrow (Tuesday, August 9th) in Baltimore’s downtown! The free event stars at noon. Info from the SHYIB folks below! Fun! Yow!

Here’s the official word:

Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!

editor William P. Tandy will regale lunching office workers, street people and sundry ne’er-do-wells with his own strange blend of humor and misanthropy as part of the ongoing summer series “Poets in Preston,” Tuesday, August 9, in Preston Gardens, St. Paul and Pleasant Streets, in downtown Baltimore. This free event begins at noon. And Hell will surely follow. Poets in Preston is a presentation of the Downtown Partnership of Baltimore, Inc. Read more about it here: http://www.godowntownbaltimore.com.

In related news,

Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore! No. 14

is coming soon from Eight-Stone Press. Pre-order your copy and read samples from the new issue here: http://eightstonepress.com/hon/hon14.htm.

For more information about

Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!

, contact me at wpt@eightstonepress.com.

Cheers,

William P. Tandy, Editor

Eight-Stone Press

P.O. Box 11064

Baltimore, MD 21212

wpt@eightstonepress.com

www.eightstonepress.com

eightstonepress.blogspot.com

www.facebook.com/wptandy

www.twitter.com/eightstonepress

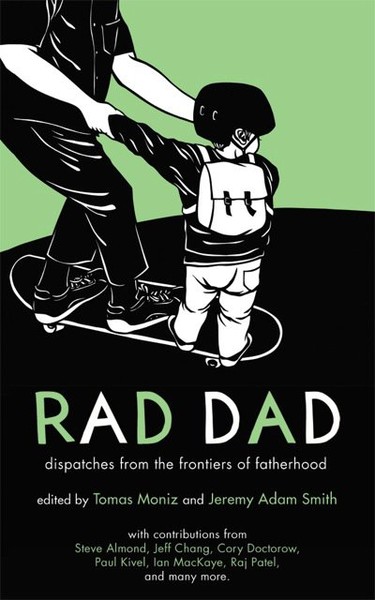

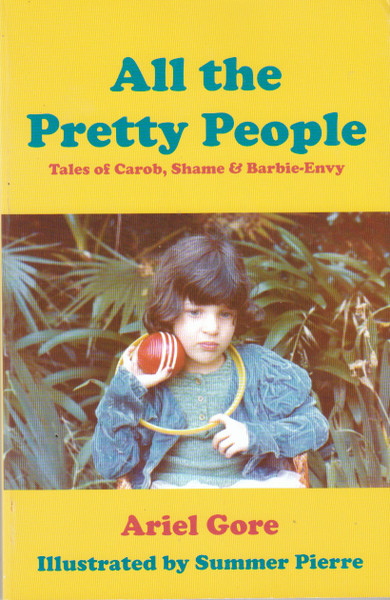

Suuuuper awesome event goin’ down at Powell’s in Portland tonight. Rad Dad editors Tomas Moniz and Jeremy Adam Smith are “opening” for Ariel Gore, who will be reading from her killer new book All the Pretty People. Check out Ariel’s blog here, Tomas‘s here, and Smith’s Daddy Dialectics site. All the fun starts today (August 5th) at Powell’s (1005 Burnside) at 7:30pm. It is free, free, free…

ABOUT ALL THE PRETTY PEOPLE This new book by Ariel Gore brings out all of the dirt on 1970s suburban hippies. Through an authentic voice, funny stories alternate between warming and saddening your soul. It’s a queer love story. But it’s also got no shortage of shame, violence, and Barbie envy. It’s about the pretty people she used to know in California—the people she wanted to be but never quite felt she was. “How was I to know that all the pretty people got their answers from TV?”

ABOUT THE NEW RAD DAD BOOK Rad Dad: Dispatches from the Frontiers of Fatherhood combines the best from the award-winning zine Rad Dad and from Daddy Dialectic, two kindred publications that have explored parenting as political territory. Both have pushed the conversation around fathering beyond the safe, apolitical focus and have worked hard to create a diverse, multi-faceted space to grapple with the complexity of fathering. Today more than ever, fatherhood demands constant improvisation, risk, and struggle. With grace, honesty, and strength, Rad Dad’s writers tackle all the issues that other parenting guides are afraid to touch: the brutalities, beauties, and politics of the birth experience, the challenges of parenting on an equal basis with mothers, the tests faced by transgendered and gay fathers, the emotions of sperm donation, and parental confrontations with war, violence, racism, and incarceration. Rad Dad is for every father out in the real world trying to parent in ways that are loving, meaningful, authentic, and ultimately revolutionary. Contributors Include: Steve Almond, Jack Amoureux, Mike Araujo, Mark Andersen, Jeff Chang, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Jeff Conant, Jason Denzin, Cory Doctorow, Craig Elliott, Chip Gagnon, Keith Hennessy, David L. Hoyt, Simon Knapus, Ian MacKaye, Tomas Moniz, Zappa Montag, Raj Patel, Jeremy Adam Smith, Jason Sperber, Burke Stansbury, Shawn Taylor, Tata, Mark Whiteley, and Jeff West.