Urban Revolutionary: An interview with Emilie Bahr

Urban Revolutions from Micheal Boedigheimer on Vimeo.

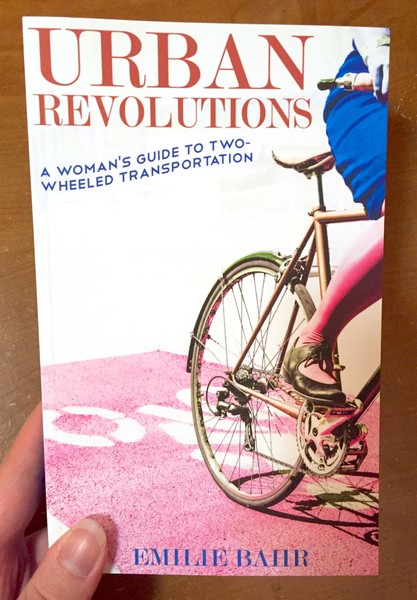

Emilie Bahr’s new book Urban Revolutions: A Woman’s Guide to Two-Wheeled Transportation just turned up from the printer, to the delight of everyone at the office. So much hard work and love went into this book. Emilie fully deployed her chops as a journalist and urban planner, her hard-won knowledge of urban transportation bicycling, and her love and knowledge of her home city of New Orleans (we’re pretty sure this is the only book out there with advice about biking during Mardi Gras!). Pretty much everyone at Microcosm worked hard on this book, and our graphic designer Meggyn actually started biking while laying it out. She’d been wanting to ride for a while and reports that this book “answered a lot of my questions… that I didn’t want to ask!” With a pre-publication track record like that, we have high hopes for the rest of this book’s life!

Emilie Bahr’s new book Urban Revolutions: A Woman’s Guide to Two-Wheeled Transportation just turned up from the printer, to the delight of everyone at the office. So much hard work and love went into this book. Emilie fully deployed her chops as a journalist and urban planner, her hard-won knowledge of urban transportation bicycling, and her love and knowledge of her home city of New Orleans (we’re pretty sure this is the only book out there with advice about biking during Mardi Gras!). Pretty much everyone at Microcosm worked hard on this book, and our graphic designer Meggyn actually started biking while laying it out. She’d been wanting to ride for a while and reports that this book “answered a lot of my questions… that I didn’t want to ask!” With a pre-publication track record like that, we have high hopes for the rest of this book’s life!

In honor of the book’s existence (it officially comes out on April 12th, and is available directly via Microcosm until then), we sent the author some questions about how and why the book came to be, New Orleans’s surprising rise to bicycling prominence, as well as (feeding a longstanding fascination of mine) the role of bicycles during and after Katrina. Read through to the end for an extra surprise!

1. Congrats on your new book, Urban Revolutions! What’s the origin story of the book—what gave you the idea to write it?

Although I haven’t always known how to define it, as a longtime fan and observer of cities, I’ve always been interested in how the shape of our environments affects opportunity: everything from transportation options to health to access to jobs (all of which, in the end, are fundamentally related). At a very basic level, the book was inspired by forging connections over the years between these ideas. It’s also inspired by my own experience as a pretty typical, car-dependent American who was woken up to another way of getting around not all that long ago and who suddenly felt (at the risk of sounding melodramatic) as though a veil had been lifted from my eyes. As I started using my bike more and more to get around, I realized that there were lots of other people out there like me – and yet also many more people, including many of my friends, for whom the idea of using the bike as a means of transport was as foreign a concept as it had once been for me. I was especially interested in this latter group and what it was exactly that kept them out of the saddle, and that became the basis for my graduate school research. I also noticed that among my friends who didn’t bike or who didn’t bike regularly (most of them women), many were intrigued by the idea of biking, but were held back by various obstacles, and a number of them really had no idea where to begin. I wanted to create a tool to help them overcome those barriers by really honing in on their specific concerns.

2. The book’s subtitle is “A Woman’s Guide to Two-Wheeled Transportation.” Why that subtitle? Is the book only for women?

2. The book’s subtitle is “A Woman’s Guide to Two-Wheeled Transportation.” Why that subtitle? Is the book only for women?

It turns out the resistance to bicycling among women isn’t unique to my friend circle. Nationally, only about a quarter of transportation bicyclists are female, a phenomenon that is not universal in the developed world and likely relates to a whole variety of factors, from social policies and norms that place more of the burden for household and childcare duties on women to very valid concerns in our car-centric environments about vulnerability to traffic crashes and crime to the fact that women are simply not as exposed to the practice, which means many of us don’t even consider it as a possibility. This book started out as a how-to guide designed to address concerns that are specific to women, though many of these concerns are also shared by men too. And I would say it turned out to be much more than a how-to guide. In the end, it’s really an exploration of the state of the American transportation landscape, how it’s changing, and what this means for everyone. I think this book should appeal to anyone who is interested in urban environments, how people get around, and who might want to brush up on how to ride and maintain a bike.

3. Two chapters of the book are devoted to your home city of New Orleans, which is one of the best unsung bike cities in the US. What makes cycling work there? What makes it different?

I said earlier that my own experience helped inspire this book, and that experience is inextricably tied to New Orleans. I write in the introduction to Urban Revolutions about hearing about what then sounded to me like a crazy plan to begin installing bike infrastructure in New Orleans. I was working as a reporter and decided to write a story about this, in part because I wanted to find out what insane people would dare ride a bike in my city. What I didn’t realize at the time was that New Orleans already had a strong bicycling culture – it had just been sailing under my radar.

In terms of what makes New Orleans different, this city has a number of inherent advantages over many other American cities, and particularly many other southern cities, when it comes to bicycling. We developed before the rise of the car, and we’ve retained a lot of the street connectivity, intermixing of land uses, and pedestrian-scale development patterns that come with that that really facilitate bicycling. It also helps that we’re flat. Moreover, we’ve seen pretty substantial infrastructure investments here in recent years that I would say have helped to advertise the bicycling possibilities that have long existed and helped make many more people feel comfortable bicycling here.

What’s also important to note about New Orleans is that we’re a poor city. Our poverty rate is significantly higher than the national average and a large proportion of people don’t have access to cars, so there are a number of people who get around by bike and have for many years before the infrastructure was installed because they have no other option. I would say that our bicycling community is very racially and economically diverse, which is increasingly true across the country, but New Orleans bicyclists really defy the stereotype of bicyclist as wealthy, white male. More and more, I notice a whole lot of women biking here too.

What’s also important to note about New Orleans is that we’re a poor city. Our poverty rate is significantly higher than the national average and a large proportion of people don’t have access to cars, so there are a number of people who get around by bike and have for many years before the infrastructure was installed because they have no other option. I would say that our bicycling community is very racially and economically diverse, which is increasingly true across the country, but New Orleans bicyclists really defy the stereotype of bicyclist as wealthy, white male. More and more, I notice a whole lot of women biking here too.

Another thing that I think really helps to set New Orleans apart from much of the rest of the world is that we have these massive street celebrations here several times a year, the most famous and massive of them, of course, being Mardi Gras. At Mardi Gras, our streets are essentially shut down to automobile traffic for days at a time, and residents are forced to reconsider our relationship with the streets, even if for a finite period. I would say that Mardi Gras and some of our other major festivals are what introduce a lot of people to the possibility of biking and help us to think about the streets as being something other than channels for moving cars as quickly as possible.

4. There’s been a lot of focus in the news lately around the 10 year anniversary of Katrina. Were you in the city during Katrina? Did bikes play a role in disaster relief or recovery? Or did the hurricane pave the way for bike infrastructure and culture in some sense?

In August 2005, I was splitting my time between New Orleans, where my boyfriend at the time lived, and Thibodaux, a small town about an hour’s drive from the city where I was working for the local newspaper. Before the storm, I evacuated from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, where my dad lives, and spent a long night until the power went out desperately trying to figure out what was going on in the city, the extent of which wouldn’t become clear to us for some time after the rest of the world knew.

So much can be and has been said about Katrina and its aftermath, but one of the things the storm revealed was just how cut off a modern society becomes when electricity and gasoline lines are severed. I sneaked back into the city about a week after the storm, and even in places that didn’t flood, it resembled something out of a post-apocalyptic novel: there was no power, no gas, military people marched in the streets. And the people who refused to leave had to rethink how they got around. You might say they resorted to old-fashioned means, using canoes, bikes, their own two feet. For many people, getting in to see their homes, especially in flooded areas, required using a bike, and some of the most powerful early footage of the damage from the storm was shot by people riding around on bike.

In the recovery from the storm, one of the silver linings has been that it’s allowed us to reconsider how we do things here. I wouldn’t say we’ve fully taken advantage of these opportunities, but one area in which it’s really caused a shifting in the public consciousness is transportation, and this is in part because the city suddenly got a lot of federal rebuilding money to redo its streets after the storm. Starting in 2008, thanks to the advocacy and creativity of a number of folks here, many of the streets that were being resurfaced were striped with bikeways for the first time. A few years later, a local city councilwoman who cares a lot about transportation beyond just moving people in cars successfully won passage of citywide policy requiring that all users – pedestrians, bicyclists, transit riders, people with physical disabilities, and drivers – be considered in rebuilding our streets. At the same time that this new infrastructure continues to take shape, we’ve experienced a surge in new people moving to New Orleans post-Katrina. Many of them come from cities with strong bicycling traditions and they have continued to spread the gospel in their adopted home, even if it’s just by example. There was a time not all that long ago when a bike commuter would have seemed like an exotic species here. Today that is definitely no longer the case.

5. Anything else I ought to ask you about?

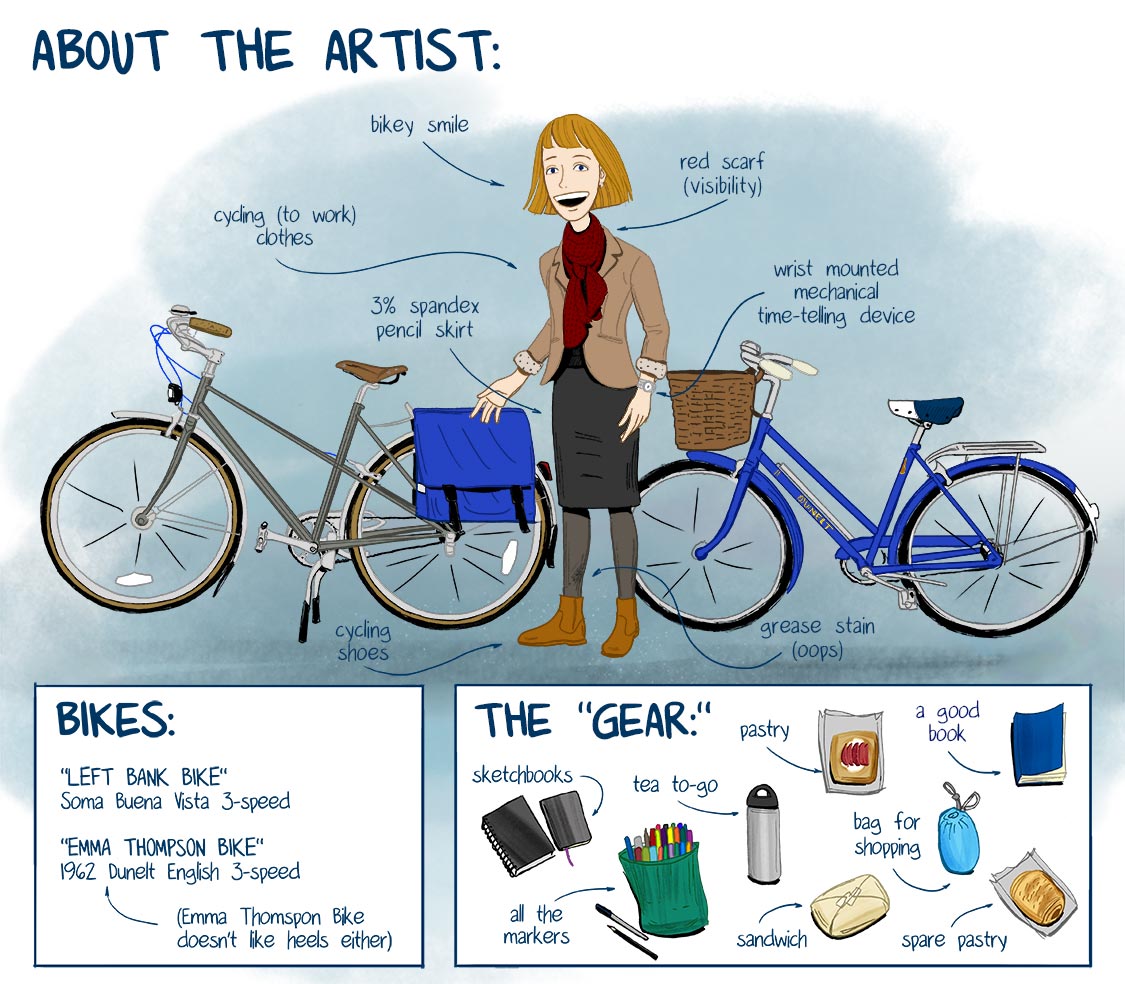

Well, I guess I could mention that I’m six months pregnant. I write in the book about parenthood as one of the obstacles many women face in getting on the bike, and I’m interested to see how pregnancy and motherhood affect my own bicycling patterns. I’m determined to continue biking but this will definitely require tweaking my routines. Already, I’ve found myself opting for my upright, Dutch-style bike over the speedier model I typically ride because it more readily accommodates my rapidly-changing figure. That said, I’m excited about the challenges and the new perspective parenthood will provide. And I’m looking forward to having a reason to invest in some of those adorable contraptions for toting around kids on bike.

This interview with Urban Revolutions author Emilie Bahr is part of a series. The last interview was with Alexander Barrett. The next one is with Kaycee Eckhardt, author of Katrina’s Sandcastles.

A year ago when we first launched the RMC, people were pretty excited about it, and would send in their short book + movie + tv + art + more experimental media (like the sounds on the bus) links and reviews every week. But participation dwindled. We started posting monthly, and then less than once a month, just when enough people had sent that in. Then, during a staff meeting, it came out that a lot of us feel a little self-conscious about what we go home and read/watch/listen to unwind. So we decided that this month we’d all be super honest and not worry about meeting some invisible cultural bar.

A year ago when we first launched the RMC, people were pretty excited about it, and would send in their short book + movie + tv + art + more experimental media (like the sounds on the bus) links and reviews every week. But participation dwindled. We started posting monthly, and then less than once a month, just when enough people had sent that in. Then, during a staff meeting, it came out that a lot of us feel a little self-conscious about what we go home and read/watch/listen to unwind. So we decided that this month we’d all be super honest and not worry about meeting some invisible cultural bar.  We ask each of our interns to review one of our books before they go. Natalie heads home to Australia next week, and left us with these thoughts on our first and (until April 2016) only work of fiction…or is it fiction? To tell the truth, we’re not totally sure.

We ask each of our interns to review one of our books before they go. Natalie heads home to Australia next week, and left us with these thoughts on our first and (until April 2016) only work of fiction…or is it fiction? To tell the truth, we’re not totally sure. Input inspires output! Here’s what we’ve been taking in this month:

Input inspires output! Here’s what we’ve been taking in this month: Alexander Barrett had only lived in our city for a year when he wrote and illustrated one of our most charming books,

Alexander Barrett had only lived in our city for a year when he wrote and illustrated one of our most charming books,  3. What’s your favorite book that you’ve read this year?

3. What’s your favorite book that you’ve read this year?

Of the fifty-plus contributors to our brand-new book

Of the fifty-plus contributors to our brand-new book  3. What’s your favorite comic that you’ve drawn? What (if it’s different) has been the most popular one?

3. What’s your favorite comic that you’ve drawn? What (if it’s different) has been the most popular one?